Apollo Investigation

Initial research by Scott Henderson with additional new findings

The gloves are off

During the 50th anniversary 2019 media flurry, a cutaway drawing of the layers comprising Armstrong’s EVA suit was published in the National Geographic July 2019 issue. The illustration and the language used to describe this suit did not disabuse the reader of the notion that it was an ‘all-in-one’. And the cutaway image of the Apollo 11 EVA suit showed the ‘integrated pressure glove’ reaching part of the way up the forearm. All well, but not so good, this is unsupported by the data published by NASA in 1969 and the Apollo 11 lunar surface photographs.

To be clear about these gloves, NASA image S69-38889 shows a left-handed gray glove with a long gauntlet cuff which is designated as the EVA/training glove. On its long cuff the list of EVA tasks is printed in two blocks at right angles to the edge of the gauntlet. Just below it is the right handed glove, its cuff has been folded back in such a way as to reveal the the ILC Industries’ data label stitched in near to the glove’s edge, this is printed parallel to the edge of the cuff. We also see this glove’s red fixing ring:

Figure 30a. Close up from S69-38889. The gray training glove and white gauntlet cuff – the blue line indicates the position of the invisible blue disconnect ring – the lower glove has the gauntlet cuff folded back to reveal the red aluminum disconnect ring (whether connecting or disconnecting the term disconnect primes in NASA speak)

According to the measurements on the NASM website a pressure glove is 27% the length of an EVA/training glove. But this EVA glove is not the length required by the manufacturer for the protection of the pressure suit fixings and the astronaut’s arms. Measuring only the white cuff, the original EVA gauntlet cuff should be some 33% longer than the cuff on this EVA training glove.

Many hands make light work

This original long gauntlet can be seen in action in the 1969 production filmed for the BBC’s science show Tomorrow’s World.14 Filmed at ILC Dover’s premises, this 6.28 minute segment aired in 1969, showed the journalist and science historian James Burke demonstrating, with the help of two ICL ‘assistants’, the various layers of what is announced as the A7L EVA suit used on Apollo 11. It included the removal of the TMG glove/gauntlet.

From the front, this conformed to that worn by the Apollo 11 crew when sitting in front of a picture of the Moon for their publicity shots (Figure 13) and it is interesting to see that the TMG front cover was peeled back by pulling at the NASA logo on the right. (As noted already, on the suits used in the EVA photos, the TMG cover was not present and the NASA logo was stitched flat to the suit). There were some relatively minor issues with this demonstration, not mentioned was that the PLSS was incomplete, the Liquid Cooling Garment had short sleeves not long sleeves, and it was inferred that that the pressure suit boots were permanently fixed to the TMG garment. Yet these boots were actually worn over the pressure suit’s rubber foot and only when the TMG was donned did the attachments to the TMG come into play.

But as it turns out all this misrepresentation was entirely necessary – due to the two very major issues this doffing exercise revealed.

The first was the removal of those very long gauntlet gloves. In order to get them off each ILC ‘assistant’ applied himself to a hand: the ‘right gauntlet’ man peeled back the very long gauntlet in one single movement, pulling it down to well over Burke’s hand until the red disconnect rings were visible. The left gauntlet man peeling from the left elbow in two movements, folded the glove twice before revealing the blue joint ring. The two assistants were obliged to use both their hands in order to manipulate the locking mechanism on the suit, to firmly grasp the aluminum disconnect belonging to the glove portion, then rotate it and pull it away from the forearm ring. Below are the various levels of the gauntlets and joint locations from 1969 to date: the red vertical lines A and B show how the gauntlet was peeled away from Burke’s left arm, making this gauntlet approximate the red-ringed EVA/training glove seen in Figure 30 above.

Figure 31. The lines on this image indicate the various lengths of glove/gauntlets in NASA photos. Gold: The NASA 1969 gauntlet worn by James Burke covers the hardware to the top of the join with the convoluted rubber joints, the manufacturer’s recommended length for a gauntlet cuff. Purple: the top of the EVA/training glove displayed by NASA and the NASM and seen in all the Apollo EVA photos; Black: the aluminum ring visible on the white TMG cover and Green: the pressure suit’s glove lock

And the blue line: from looking at S69-38889 close up (Figure 30) without knowing anything about these glove shenanigans – this is where the fold back infers that the wrist-glove connection of this EVA training glove would be located – and the mismatch is what originally alerted me to these Apollo suit anomalies.

Below is another picture showing the same principles:

Figure 32 (above). EVA/training glove/gauntlet placed beside a close up view of Aldrin (from AS11-40-5903). It shows the difference in gauntlet cuff length between this glove and the one that Aldrin is wearing on his right hand. The black strap of the Omega watch diverts the eye from the black ring visible above this much shorter cuff.

The glove on the other side of Aldrin’s hand shows how the black ring is located just under the pressure valve and just above the hem of the TMG sleeve. It also shows how the red aluminum disconnect ring on the arm relates to the as yet unconnected red aluminum fixing on the glove.

Compare the black ring in the above picture with the image (Figure 32a left) showing the black ring on Armstrong’s A5L training suit.

Leaving Astronaut Burke without his gauntlets but still standing in his suit, we turn to the gloves photographed during Apollo 11, (Figure 32b left). The NASM has three photos of Aldrin’s EVA gloves on its website. All are listed as ‘flown’. Photos top and bottom of Figure 32c both look like a pair of the Neoprene protection gloves worn over the pressure gloves when in an unpressurized CM or LM.

Leaving Astronaut Burke without his gauntlets but still standing in his suit, we turn to the gloves photographed during Apollo 11, (Figure 32b left). The NASM has three photos of Aldrin’s EVA gloves on its website. All are listed as ‘flown’. Photos top and bottom of Figure 32c both look like a pair of the Neoprene protection gloves worn over the pressure gloves when in an unpressurized CM or LM.

Sandwiched between them is a Chromel-R EVA/training glove together with a photographer’s color scale lying alongside it – as if to draw attention to this variation of color. It calls to mind the tripod gnomon seen in several of the anomalous Apollo images. Then, the designation of ‘flown’ for all three juxtaposed with the ‘training’ glove, put into question the actual arena in which these gloves were used. Taking the gnomon as a hint to think about these color differences more poetically, suggestions of whistle-blowing again arise – the Neoprene gloves with blue fingertips are reminiscent of the liminal space between sandy land and blue sea; the dark gray EVA/training glove with blue fingertips recalls Earth-based lunar EVA training sessions.

If the NASM website glove data and the photographs in the museum are whistle blows they are getting heard. If all the oddities and muddles are an attempt to fix continuity errors – things are about to get a whole lot worse.

Blue Tips and Hints

From a practical point of view the protective outer glove had blue fingertips for a specific reason. Made of silicon, they were intended to provide extra sensitivity for the astronauts and thereby facilitate the execution of their EVA tasks. Controversially, it is claimed by some astronauts that these gloves actually damaged the astronaut’s fingertips and nails. The Apollo 15 record has accounts of Dave Scott complaining of blood under the nails and fingertips rubbed raw after their lunar EVA work. A photograph of Scott’s bloodied fingernails apparently taken at the post-mission press conference, is now online.15

Notwithstanding evidence coming in from the ISS of delamination occurring during micro gravity EVAs, even by 2019 there is not enough data to fully understand why this is happening. However, it is the Apollo 15 flight crew who decided to play the Air Force (Fight) song during the most critical moment of their mission plan – ascent from the lunar surface – and didn’t care that it interfered with any critical flight communications from Earth. Given the Apollo 15 crew’s previous shenanigans one might ask if this fingertip scenario is yet another joke, a whistle blow, or another attempt to confuse lunar EVAs with LEO micro gravity. BUT Scott’s scenario is actually more plausible when associated with long training sessions here on Earth. Wearing cotton gloves under an EVA/training glove, without a pressure glove underneath, any slippage could aggravate the fingertips and nails of a hand under duress.

Back to Buzz, below are close ups of Buzz Aldrin gripping the handrail while descending the ladder wearing his ‘flown’ gloves. This is significant as we will see later regarding the restricted grip available with the Apollo glove:

Figure 34. Aldrin gripping the handrail of the LM ladder wearing the gray training gloves – his cuff reveals that even though the gauntlet has NOT been folded back, the black ring on his TMG is clearly visible:

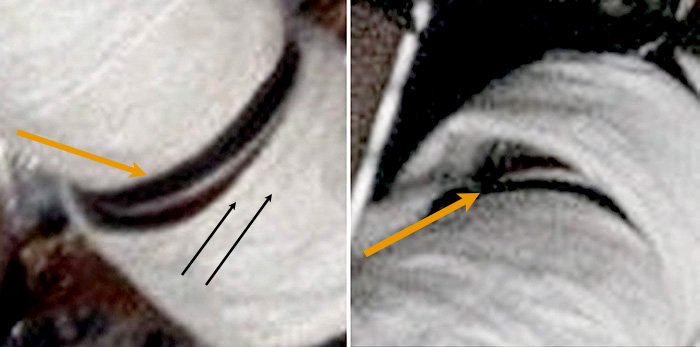

Figure 35. Close ups of Buzz Aldrin’s cuff revealing the black ring on the TMG suit that should not be visible – the opportunity for dust and debris to enter this glove is obvious, and the pressure disconnect ring below it could lock up due to dust infiltration – note also the two faint lines on the cuff stitching (left image)

If the Apollo TMG glove really was of integrated pressure and gauntlet as stated, it begs the question as to how the astronauts were going to manage when returning to the LM with filthy, dusty gloves. A gauntlet – should it ever be in a real lunar EVA situation – would only need to be pulled on over the top of the actual pressure glove before leaving the LM. And in order to avoid dust contamination, a dirty EVA gauntlet could easily be pulled off prior to opening up the LM, without the astronaut losing pressure. It is even asserted in some accounts that the Apollo 11 astronauts did indeed throw out their version of the EVA gauntlet before departure from the lunar surface. And if that is so, it begs the question as to how the NASM can advertise Buzz Aldrin’s Chromel-R gray glove as ‘flown’.

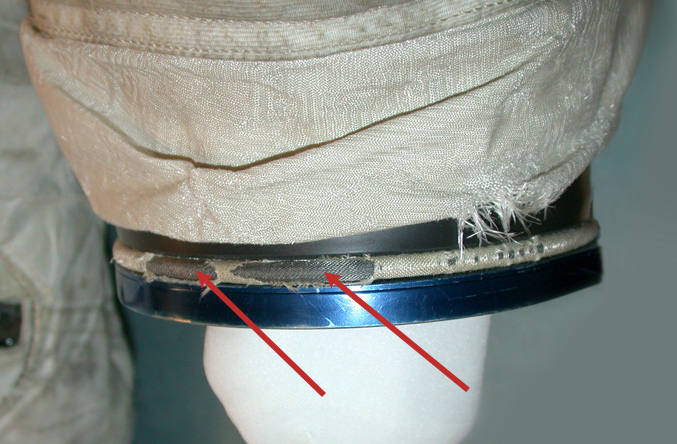

And while on the subject of wear and tear, here is an Apollo 14 photo of Ed Mitchell’s TMG:

Figure 36. Noticeable wear around a suit ring supposed to be impervious to the lunar environment for at least the duration of the Apollo 14 EVAs – and note the black grip ring that clamps the TMG to the joint ring

Remembering that Ed’s suit had that white ‘on location‘ zipper, look at the wear around the disconnect ring of the TMG above – the wear looks like months of use, not some nine hours of lunar EVAs ascribed to their mission. But that’s maybe why we have the stories of angular dust particles on the Moon. (And melting boots – apparently the blue-soled over-boots melted in the hot temperatures of the lunar surface – yet still managed to make all those crisply-defined footprints).

Here on the left an exposed black ring on the TMG suit is clearly visible. A section of the cuff looks to be attached to the black ring along the inner wrist, at point A, thus causing the gaping at the outer side of the wrist. Notwithstanding the extremely light tone of this glove, the fixing location is obvious.

Here on the left an exposed black ring on the TMG suit is clearly visible. A section of the cuff looks to be attached to the black ring along the inner wrist, at point A, thus causing the gaping at the outer side of the wrist. Notwithstanding the extremely light tone of this glove, the fixing location is obvious.

According to NASA’s own documentation, this glove with a short cuff cannot be the gauntlet intended originally for use on the Moon. I think that as a result of continuity/disasters (whistle-blowing spotted far too late) it was necessary to abandon the original extra-long version and adopt the EVA/training glove as the ‘actual EVA glove’. One could justifiably refer to a redesign process for its less than optimal length. Unfortunately, that justification is not going to hold for long – as we shall see.

I have concluded that for those not in the know, everything had to match a valid function on a real space flight. This glove (with a shorter cuff which was attached to the back ring on the training suit) was used everyday for training and it was a copy of the CM in-house Neoprene glove. Discontinuity errors in its regard were dealt with by folding the cuff back on the display gloves. This adopted shorter cuff glove/gauntlet design made it far easier to don and doff the gloves during rehearsals and prolonged photographic studio and filming sessions.

The inevitable conclusion therefore is that all the Apollo EVA photographs are of the costume used for rehearsals and studio simulation photography here on Earth. But the need for training and photography in studios, where they didn’t need, or want, a pressure garment meant that the training suit must itself be equipped with the solid helmet and forearm disconnect rings in order to practice wearing helmets and gloves while working.

This is where we meet the second of those two major issues encountered by Astronaut Burke of Tomorrow’s World.

After the long gauntlets had been removed it was time to remove the suit itself. The two ILC assistants positioned themselves in front of Burke, one to each side of his centre line, and having undone the suit along its spine they pushed Burke down into a half-bent position, and proceeded to alternately tug at the suit, and shove at Burke – who might have been regretting his part in the whole affair by then. At times they seemed not know how to proceed, as they couldn’t get a proper grip on the suit – the helmet ring seemed to be inhibiting their movements.

Finally they got it over his head and off. Which is when we see he wasn’t even wearing a pressure suit, and all that shoving came into focus. Normally the TMG would not have a hard visor ring attached to it – nor would it have had a black zip, but Velcro fold-over fastening and a Chromel-R patch on its back.

Figure 38. Square of Chromel-R used on the back of the TMG – no longer produced, NASA purchased 50 yards at $5,000.00 a yard for Apollo

The ILC chose instead to show a plain white back to their suit with an ordinary black zipper although recalling the specialist pressure zip, this was on a TMG incapable of retaining any pressure – an irony beyond. This is a completely misleading demo on how the Apollo EVA spacesuit was actually configured. But as Burke commented, “If you can get this [suit] on, then you deserve to go to the Moon.” Yes, indeed, but you wouldn’t get there! Because the white metal neck disconnect ring was from the Mercury and early Gemini flights; the black zipper informed those in the know, including me in this instance, that Astronaut Burke was actually wearing a Gemini suit and not an A7L Apollo suit.

And the fact that the white metal collar was attached to this TMG told me that this too, was a costume. Whether this particular mix-and-match combo was a cry of despair from the ILC or wool over the eyes of the sheepish viewer is up for discussion.

Time’s up!

If all the above requires anything further to persuade you that something is seriously awry with the Apollo record, here again is a close view from the famous picture of Aldrin standing alone:

Figure 39. AS11-40-5903, Aldrin standing on the lunar surface wearing the gray glove/gauntlets – note the much longer left hand glove cuff. Neither of these gloves correspond to the original full-length EVA gauntlet published by NASA in 1969, but look closely: Aldrin’s left hand with the EVA/training glove is pointing to his right wrist, it could be about his watch but he also seems to point to the totally incorrect shorter-cuffed Neoprene right glove with the exposed black ring

What was happening might or might not be Aldrin’s expressed intention, but it rather appears as if this is a clear whistle blow: the difference in length between these two cuffs is again 27%. It can be concluded that his right glove is modelled on the CM in-house shorter Neoprene glove. While his left glove/gauntlet is modelled on the exhibited gray EVA/training glove. The fact that these two gloves could co-exist on the arms of an astronaut supposedly on the lunar surface is a total nonsense.

All of the confusion over suits and gloves, between what we see and what is really going on, has arisen for one key reason. Checking against other data, it was soon clear why there is such a muddle around the Apollo spacesuit. Experts in the field of spacesuit construction considered the ‘soft suit’ design inadequate for the performance of any EVA – either in LEO or on the lunar surface.

Below is a list of the problems found with this ‘soft suit’. This late 1961 study (two-thirds of the way through the Mercury program) was published by the Russian Zvezda group. It was based on various data resources, including translated US publications on spacesuit research and design, the spacesuit studies by Herman Oberth and the experience of the Russian Zvezda group. During the space race most development was project oriented, but the Zvezda formed its own separate R&D group in 1952. Its scientists studied the evolution of full pressure high altitude pilots’ suits from the 1930s onwards, with the intention of creating a viable space suit and also a lunar EVA suit.16

By 1961 the conclusion reached was that the soft full pressure suit plus a removable PLSS was not the optimum solution for working outside a spacecraft, NOR on the lunar surface. The principle reasons for this were:

-

Considerable differences in dimensions and torso shape of the pressurized and unpressurized suit;

-

Difficult donning/doffing and sealing of the suit enclosure;

-

Suit elongation (so-called ‘ballooning’) under positive pressure due to fabric deformation and distortion of the suit enclosure shape;

-

Limited range of suit enclosure adjustment to fit different human shapes;

-

Necessity of backpack restraint system and difficulty of its operation;

-

External communication lines between the suit and the backpack,

-

Difficulty of attaching suit controls to the soft torso enclosure.

The Russians concluded that:

The preferred design by far was the HUT, a hard upper torso having a built-in LSS with controls attached to the torso and arms with gloves and leg enclosures made of soft materials. The Russians had added that when creating their HUT model, as is known from the literature, the rigid suit projects of the US Litton company and the Oberth spacesuit projects were of no use for this task.

Figure 40. Typical modern EMU space suit – ILC Dover (Tom Lehman/WBOC)

This EMU has just a single ring connection at the waist mating the lower soft torso to the upper semi-rigid torso

The large semi-rigid space suits worn today by US astronauts outside the ISS are derived from the Russian HUT suit. The US call their version the Extravehicular Mobility Units or EMUs and this has led the public today to confuse the attributes of these ISS suits with the Apollo EMU.

Figure 41. Close view of the upper rigid component of a modern EMU

It is noteworthy that the suits designed today have gloves with a wrist cuff level incorporated into them, but with an overall length matching that of the original Apollo gauntlets. In fact as these ISS EMU gauntlets extend well up the arm (parallel with the top of the notepad) to the robust shoulder padding providing additional radiation protection on the soft part of the suit. And these suits are only going to be remaining below the Van Allen radiation belts.

Figure 42. EMU suits today have gloves with an incorporated wrist cuff level

There is a big difference between a suit designed for use in low-Earth orbit, where a micro gravity environment obtains and an EVA suit designed for the 1/6th gravity of the lunar surface. But back in 1965, during Gemini and on into Apollo, confusion set in, for the public at least, when NASA adopted the term EMU for the Apollo suits – applying it to both the intravehicular suit, as well as the EVA suit – thereby conflating these two different space environments in the public’s mind.

Maybe that was the idea, because from the evidence thus far the Apollo suits really did have some serious reliability issues, which made a crewed trip beyond LEO and an EVA on the Moon as impossible in the 1960s – as it still is today. The Apollo soft suit has now been dumped (along with virtually all the Apollo hardware). Consigned to museums and the history books today – but back in the USA in the 1960s, despite the Soviet views on such matters, it was decided to continue the Apollo program with the soft-suit shuffle.

Perhaps it didn’t matter a jot if the show was the thing and they weren’t actually going very far after all.

Figure 43. Space suit engineer Amy Ross MSc demonstrates restricted hand movement and grip during her tutorial: Glove 101 (NESC Academy)

As for the Apollo pressure glove’s mobility, charitably, Amy Ross considers that the Apollo astronauts did very well considering the limited capabilities of the time – and observes that with only limited motion in the fingers they would also have had great difficulty in managing any dexterity in their hands. Amy Ross stresses that,

What that means in practice is that when this is pressurized there is little to no, mostly no mobility below that joint… So if you see them drop their hammers, it’s for a good reason.

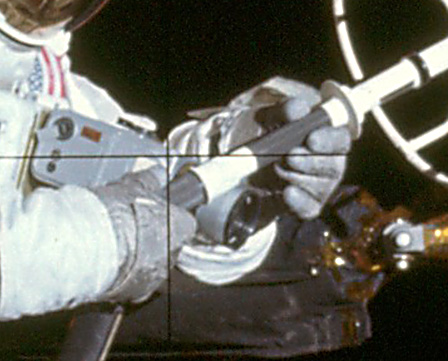

You may well ask that if there is “mostly no mobility” when wearing a pressurized glove, how did the Apollo astronauts grip handrails, tools and twist slim flagpoles. Below is a close up from image AS12-46-6790, Alan Bean during Apollo 12 uses the fuel transfer tool allegedly wearing his pressurized gloves and somehow he manages to successfully hold and grip the tool rod:

Figure 44. Alan Bean (Apollo 12) using the fuel transfer tool despite the pressurized gloves having ‘mostly no mobility’

Figure 34 (repeated). Buzz Aldrin gripping the handrail while descending the ladder

As for their movement, Amy Ross thinks that the hopping and stiff walking was due to the limitations of the suits causing locked hips. While agreeing somewhat with that – it’s worth pointing out that wearing an under harness with a connection to a weight-relieving wire suspension rig would more likely result in the various odd motions ascribed to these astronauts. But that’s another story, see Appendix 1.

Figure 45. On October 16, 2019 NASA revealed the new Artemis lunar EVA suit, a cousin to the ISS suits. This suit confirms the validity of the Zvezda group findings and bears no resemblance to the Apollo suits. NASA/Joel Kowsky

Figure 45. On October 16, 2019 NASA revealed the new Artemis lunar EVA suit, a cousin to the ISS suits. This suit confirms the validity of the Zvezda group findings and bears no resemblance to the Apollo suits. NASA/Joel Kowsky

Two timing

Today we think of Buzz Aldrin as someone who wears numerous rings and a lot of crystal jewelry – who also has a serious interest in watches – he often wears two on the same wrist. He has been known to wear a regular necktie and a bow tie at the same time on official NASA business. Whether this is simply Buzz being Buzz or a symbolic reference to his two space missions, when it came to the 50th anniversary Buzz was notably absent from the July 16th commemoration of the Apollo 11 launch at the Cape.

So it could be that Buzz is referencing the twins of Gemini rather than Apollo and even Gemini 12, High Noon, his own mission.

Over the two days of July 16 and 17 he did tweet two photos and comments about Apollo 11. The first showed an unsmiling tense Buzz, looking straight to the camera lens his arms and hands thrust towards the camera. His left hand was angled towards his right hand. The second showed a joyful smiling Buzz, celebrating his days of being an Air Force pilot. Another set of ‘spot the difference’ photos.

On July 19 Buzz did turn up at the Oval Office for an Apollo 11 moment, during which a discussion about the future of space travel ensued. Buzz Aldrin, disappointed with the state of human space exploration over the past 15 years, is an advocate of getting to Mars directly, Collins also voted for the Mars direct approach. NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine, noting that “Because of the planetary alignments, launches to Mars can occur only every 26 months and even then the trip is seven months each way”, preferred the Moon first, Mars second approach. President Donald Trump, not in the loop, asked “What happens if you miss the timing? They’re in deep trouble?” And added “You don’t want to be on that ship.”

Summary of key complications and shortcomings

- One of the absolute No-Nos for current spacesuits is the use of zippers

- Pressure suit disconnects were difficult to actuate upon LM entry and next EVA preparation

- The Apollo space suits were not fit for purpose

Conclusion

It is abundantly clear that the black ring adjoining the wrist disconnects on the TMG should not be visible in the lunar surface photographs. No doubt this was done in the expectation that at some point in the future this anomaly would be investigated.

This space suit business is highly confusing and complex – which is in all probability intentional. We have shown that NASA refers to the ‘Apollo spacesuit’ as if it were an ‘all-in-one’ item, but back in the 1960s this was not the case. A crewed Apollo mission required three basic configurations of dress, all designed for different situations. For the purposes of the Apollo program’s success, these mix-and-match items were reduced down to one single costume for the Apollo photography – and this included all the filming with astronauts and/or actors as well as the generation of all those thousands of still images. If the shorter-cuffed glove made it easier to don and doff the gloves during rehearsals and prolonged photographic studio and filming sessions, the whole issue of gloves provided opportunities for whistle-blowing by those who cared (see Appendix 1).

Until the serious problems with Apollo have been recognized for what they are, no spacecraft are going anywhere of consequence – and space engineers reworking the technologies from Apollo in order to build Orion and begin to fulfil the Artemis segment of the former Constellation program are beginning to find that out for themselves – as can be read elsewhere on Aulis Online. The spacesuit anomalies presented here are further demonstrations of obvious fakery of the record.

In 2010, Buzz Aldrin said that the Apollo Moon landings were not a historic event, but a stunt, and that going to Mars would be a historic event.17 The spacesuit anomalies presented here are further demonstrations of obvious fakery of the record. These criticisms are not written to denigrate the Apollo astronauts caught in a web not of their making, but in an effort to help those who, like Buzz Aldrin, would like to realise the dream of sending astronauts to Mars, safely and honestly.18

The final word goes to Gene Cernan, in 2016:

“I’ve said for a long time [and] I still believe it, it’s going to be – well it’s almost 50 now – but fifty or a hundred years in the history of mankind before we look back and really understand the meaning of Apollo,” stated Cernan in 2007. “We did it way too early considering what we’re doing now in space. It’s almost as if JFK [President John F. Kennedy] reached out into the 21st century where we are today, grabbed hold of a decade of time, slipped it neatly into the 60s and 70s and called it Apollo.” 19

Scott Henderson and Aulis Editors

Aulis Online, September 2019

Appendix 1

Having concluded that these suits were actually costumes for photography and filming, another item would have been needed to achieve the 1/6g effect. The astronauts would have to appear to be walking and working under a much reduced gravity in the Apollo imagery – rather difficult to achieve solely with slow motion filming. One key component of the under garments actually worn for the Apollo photography would have included an under harness for relieving the performer’s weight.

Having concluded that these suits were actually costumes for photography and filming, another item would have been needed to achieve the 1/6g effect. The astronauts would have to appear to be walking and working under a much reduced gravity in the Apollo imagery – rather difficult to achieve solely with slow motion filming. One key component of the under garments actually worn for the Apollo photography would have included an under harness for relieving the performer’s weight.

A means of achieving this result would be to wear a harness like the one in the illustration. Worn around the hip a pair of wires would be attached to either side of the hip joint at the lower back, linking to a single wire which would be passed through an aperture in the upper back of the costume. This would enable the astronaut/actor to have up to 45% if his weight reduced for the full effect.

A single 5mm approx monofilament of support wire connected to the body harness would in turn be connected to the special weight-relieving rigs running above the studio sets, as suggested in the illustration top left.

The purpose of such a rig would be to provide a counter weight which would average around 40% of the weight of the astronaut/actor, although depending on filming speeds relative to the distance of the astronauts from the camera, other counter weight percentages could also be selected.

This arrangement would facilitate the wire-assisted simulation of 1/6g and thereby enable effective and convincing creation of the TV coverage and still images – including those infamous jump salute photographs.

(For more details of this please view the Smoke & Mirrors highlights video starting at 24.00) and see also Jack White’s study.

In order to use a version of the A7L suit for simulations and studio photography/filming a suitable lightweight PLSS would require little more than a fitted radio transmitter/receiver and a cooling fan to circulate air, with batteries to power them. A plastic outer case covered with the white abrasion material would do the job. There was a square opening at the bottom of the PLSS that would an ideal air intake point.

The liquid cooling garment would not be required, nor of course would the pressure suit need to be worn. A bubble helmet wouldn’t be needed under the outer visor helmet. The astronaut/actors would therefore be able to flip open the visor between takes and set ups. The gloves wouldn’t have to be securely connected – they would only need to be fixed/pinned at the gauntlet. Such an arrangement would then permit air to pass through the suit sleeves – and similarly with the boots. The original fly flap at the front of the suit would be essential for bathroom breaks. And of course the sunglasses pocket was intended for people like me, Scott, to write songs about these shenanigans.

Appendix 2

Regarding the fact that the Extra Vehicular Visor Assembly deformed, draping over the bubble helmet under Thermal/vacuum testing, the account from NASA space suit expert Jim McBarron tends to fall down on several points. Tracking this outer helmet evolution reveals that it was already understood well before March 1969, that the EVA helmet was not fit for purpose. Because the NASA Apollo 9 mission report already has that (our Figure 3) apparel illustration which shows a soft TMG covering around the neck of the EVA helmet. But then Mc Barron’s presentation ascribes the wrong dates to the 1968 Apollo 7 (a year too late, and a week short) and the 1969 Apollo 10 (a year too early) – which no one at his 2015 presentation seemed to notice. But something else was picked up, and it was a good question. McBarron was asked why his photos of Apollo missions 8 and 10 showed two of the astronauts wearing EVA suits, when no one was going outside the craft.

Jim Mc Barron, sounding as if he was making it up on the hoof, replied that the suits were changed just before the mission, patches were added and connections removed. Sensing that wasn’t working for the questioner, he added that this was done back at ILC – and not ‘in the field’ (at NASA). This answer didn’t really work either, not least because ILC Dover documentation clearly states that the Apollo 8 crew were issued with special Intravehicular spacesuits, as they were trying out a new Super-Beta covering on the these suits and they did not have the EVA connectors as they were not going on an EVA.

The questioner certainly knew that; and that NASA photos of the Apollo 8 walkout (and Apollo 10) show the astronauts wearing the EVA TMG; and that when the 1975 ASTP mission had walked out, they all did wear intra-vehicular fittings, because they weren’t going outside either! (Figure 28.) So there was still a slight air of disbelief and puzzlement lingering in the room, which McBarron must surely have registered because he moved swiftly on to the next costume change, apparently instigated after Apollo 10. With more gear not fit for purpose as the date for Apollo 11 approached, the sun visor for Apollo 11, (which on Figure 13 can be seen as transparent) was changed to a Polysulfone material. If it was this change which rendered it opaque, that too was done before the Apollo 9 photographs were taken.

Nothing is what it seems in the evolution of the Apollo spacesuit and its accessories. However, a new phase of the Apollo program must have been reached because there had been another change of name. The hard EVA helmet of Apollo 9 was dubbed the the Lunar EVA (LEVA) for Apollo 11. And that opaque sun visor proved to have other useful qualities: it was impossible to see who or what was inside the suit, and it gave the photographers all those arty visor reflection shots seen in the Apollo 11 EVAs.

Footnotes

- The Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum portal

-

Apollo 11; The NASA Mission Reports, Robert Godwin, Volume 3, p.215, Apogee Books Space Series Collector’s Guide Publishing Inc., Canada. Based on the NASA Apollo 11 Mission Report published November 1969. Vol 1 October 1999, Vol 2 June 1999, Vol 3 April 2002. Figure 1b which shows the order in which each set of garments comprising the EMU were donned is featured in Apollo 9: The NASA Mission Reports – same author and publisher, January 1999. Apollo 9 was scheduled for March 1969. NASA provides a full description of these layers.

-

Four references: Apollo Operations Handbook, Extravehicular Mobility Unit,

Vol II suit AP12-15 EMU v2, October 1969, and Apollo Experience Report: Development of the Extra Vehicular Mobility Unit, NASA Technical Note, NASA TN D-8093 p.12, November 1975, and Wikiwand Apollo/Skylab.

-

The International Latex Corporation (ILC Dover) has a history of spacesuit development here: ILC states that Apollo 8 & 10 used CMP suits for all three astronauts as they were not gong outside, but NASA photos of these missions show that the CDR and LMP Pilot wore EVA suits – where were they going?

Also see Appendix 2 for more on this matter. -

1998 NASA document Suited for Spacewalking, p.95 asserts that “Mercury demonstrated that humans could live and work in space.” Which is a real departure from the facts: the Mercury program clocked some 54 hours over six missions. Of the six Mercury flights the first two lasted some fifteen minutes each; the next two each orbited for nearly five hours; the fifth orbited for nine hours; the sixth flight, orbiting for some 36 hours was not without technical problems. NASA then states, “Gemini pioneered space flight technologies for rendezvous, docking and spacewalking”. Any pioneering here is strictly limited to the US. While NASA was running the Mercury program, the Russians had orbited a single flight for over 118 hours and begun tackling rendezvous and other tasks.

-

NESC Academy – Jim McBarron tutorial: Apollo Space Suit Development, A7L Suit Requirements and Design Details, and NESC Academy – Jim McBarron tutorial: Apollo A7L Spacesuit Certification and Mission Operations Details.

-

Bennett & Percy, Dark Moon: Apollo and the Whistle-Blowers, Aulis Publishers, 1999.

-

Ross is lead spacesuit glove engineer since 1996, her NASA glove presentation Glove 101 was held on August 4 2015. NESC Academy – NESC Academy – Amy Ross tutorial: Glove 101.

-

The Ingenious Invention to Better the Button, BBC TV, Cathleen Lewis quote, March 2017.

-

Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum Washington, DC.

-

The Apollo Experience Lessons Learned for Constellation Lunar Dust Management, NASA, September 2006.

-

Clip from Moonwalk One ca.1970 255 HQ, and also The Women from International Latex Company.

-

Reaching for the Stars; the Illustrated History of Manned Spaceflight, Peter Bond, Foreword by US astronaut Harrison Schmitt, 1994, Cassell.

-

James Burke Demonstrates the Lunar EVA suit, Tomorrow’s World, BBC TV, 1969

-

Apollo 15, Lunar Surface Journal.

- Russian Spacesuits, Springer Praxis Books in astronomy and space sciences, August 2003.

-

Buzz Aldrin: “The guys who go to Mars and begin to build a colony there are going to be immortalized. It’ll be far more important than a couple of conflicting nations on Earth doing a few stunts in space to try and outdo each one. Sending a couple of guys to the Moon and bringing them back safely? That’s a stunt! That’s not historic.” Vanity Fair, Eric Spitznagel, June 25, 2010.

-

The Kranz Dictum: post Apollo 1 disaster Gene Kranz made a long statement to his team which included these words: “Every element of the program was in trouble and so were we. The simulators were not working, Mission Control was behind in virtually every area, and the flight and test procedures changed daily. Nothing we did had any shelf life. Not one of us stood up and said, ‘Dammit, stop!’ I don’t know what Thompson’s committee will find as the cause, but I know what I find. We are the cause! We were not ready! We did not do our job. We were rolling the dice, hoping that things would come together by launch day, when in our hearts we knew it would take a miracle. We were pushing the schedule and betting that the Cape would slip before we did.”

- Cernan, during his presentation with the Neil Armstrong Outstanding Achievement Award by the National Aviation Hall of Fame, in part to honor his advocacy for “personal empowerment and development, especially among youth,” as well as his support for the revival of U.S. human space exploration.

![]()

This article is licensed under

a Creative Commons License

We consider that this analysis falls under the ‘fair use’ laws of the USA and the United Kingdom, and any copyrighted material is included on a not-for-profit basis for research, discussion and educational purposes only

I came across this video accidentally. I’m posting it to demonstrate how far humans will go to deceive their fellow Americans AND the world population. There is no need to watch it from start to finish. Just pop in anywhere and you’ll get the idea. It’s so well scripted and edited, the average Joe and Jane will not recognize the total fantasy it represents. It’s truly staggering.

I’m speculating they are now at this point of fantasy because of the advance in video fakery …so, creating any future ‘space’ adventure will be relatively simple compared to 50 some odd years ago.

No doubt they will go to Mars….in a Hollywood basement!

Good luck in tolerating as much as possible.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n9xyMaUAyYI

This is the best summation of the fairy tale we live in ——ever.

ALL I WANT FOR CHRISTMAS IS THE TRUTH

https://www.theburningplatform.com/2012/12/03/all-i-want-for-christmas-is-the-truth/

“Here’s The Longest People Have Survived Without Air, Food …

http://www.sciencealert.com/here-s-the-longest-people...

Jun 10, 2016 · Here’s The Longest People Have Survived Without Air, Food, Water, Sunshine, or Sleep. Every person and situation is different, though the ‘rule of threes’ gets at the desperate nature of what our bodies need: 3 minutes without oxygen, three days without water, three weeks without food. But some extraordinary members of our species have broken and redefined these and other limits of human survival.”

The acceleration of gravity on the Moon is about 1/6 that of the Earth. Roughly the acceleration of gravity on Earth is 32 ft/sec(2). On the Moon it is about this number divided by 6 or about .5.3 ft/sec(2). Where does oxygen come from on Earth? Plants. So far as we know no plants exist on the Moon to produce Oxygen. But even if they did, the gravitational attraction of the Moon, being only about 1/6 that of Earth, would not be strong enough to hold the oxygen molecules around the surface of the Moon; in other words they would leave and move into outer space. The reason they do not leave Earth is because the gravitational attraction of Earth, being 6 times stronger than the Moon, holds most of them in a cloud around Earth. It is this oxygen based atmosphere which led to the evolution of the so called “higher” forms of life as we know them on Earth, the highest being Man, followed by the various lower forms of animals and plants, although America’s greatest author and writer Mark Twain argued that Man was the lowest of all the animals on Earth. He presented a “proof” for this claim in a great book published after his death, “Letters from the Earth” about 1938.

Higher forms of life did not always exist on Earth either. This took time to evolve. The early stages of Earth were similar to the Moon. The lowest living forms called fermentation, developed first without any oxygen. This is the kind of life you see when you look down into a closed milk bottle with some of that gray’blue stuff on the bottom which grew without oxygen. Somehow this stuff evolved into higher plant life first, which began to provide early low levels of oxygen into an atmosphere.

After the passage of millions of years enough oxygen developed to foster early animal life and eventually presumably the “highest” human life….MAN.

Observe that if fool man continues to destroy all the plant life on Earth, and continue to pollute the vitally oxygen based atmosphere, vital for all human and most animal life, man is basically committing suicide. Some folks argue this might not be such a bad outcome since, as some folks argue, man is a worthless piece of garbage. Basically Mark Twain argued that the best outcome would be for man to be obliterated from the Planet so the higher plants and animals and Earth could survive in peace.

Man was designed to live in an oxygenated environment. Three minutes deprived of Mother Oxygen and Man is a Dead Man. It is a non trivial problem to design the apparatus for Man to survive in an environment without Oxygen like the Moon. A mountain of evidence and facts shows that NASA dismally failed but lied about that failure. Disgrace is far too polite a word for this total betrayal of our government agencies to its citizen taxpayers: Shame, shame, shame on them.

Many thanks to Scott Henderson and Distinguished Professor Jim Fetzer, Ph.D., for posting this article about lying and cheating to all our good citizens by criminals in NASA. What a shameful disgrace they are