Apollo Investigation

Initial research by Scott Henderson with additional new findings

Figure 1. Pressure garment, 1932 |

Introduction

Joining the Dots. Research strongly indicates that the space suits worn for the Apollo photographs and TV coverage from the Moon were simply costumes designed for simulation and photography.

Meticulously detailed studies of the evidence reveals that Armstrong and Aldrin’s suits, as worn in the Apollo 11 photographs, were copies of the Apollo space suits designated for an EVA on the lunar surface. It is asserted that the details within these photographs demonstrate that these ‘accessorized costumes’ were worn without their pressure suits and could never have been used by anyone who was actually on the Moon – they didn’t have the seals required to enable them to be reliably pressurized and withstand an external vacuum.

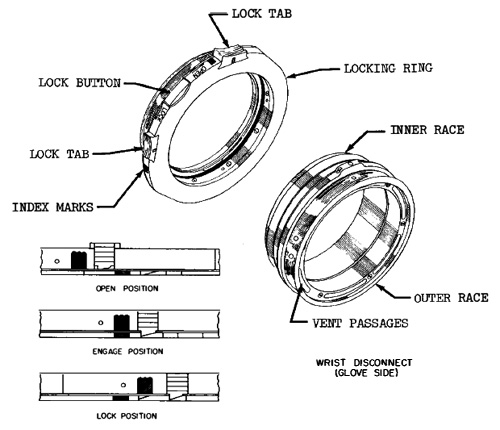

Figure 2. The fact that this ring is exposed in the Apollo 11 photos prompted this investigation. As we will see, it should have been fully covered by the glove/gauntlet.

There were numerous problems with the suits as worn in the Apollo 11 lunar surface imagery and in all the subsequent missions. So much so, that I had concluded that “clothes do not maketh the Moon Man”. Then, during Apollo 11’s 50th anniversary I noticed that the Apollo spacesuit was presented to the public inaccurately in both words and images.

Although this inaccuracy is partly due to the fact that across the Apollo record references to the suits used on the Apollo program are unclear, with exhibited items either wrongly labelled or presented differently relative to what we see in the Apollo imagery or read within the NASA documentation.

Such inconsistencies at the very heart of the Apollo record can be taken in two different ways: 1) either there are those trying to mitigate the effect of the Apollo critics by creating so much confusion that the public just turn away; or 2) this confusion is intentional, achieved by deliberately conflating different aspects of Apollo spacesuits – and that means whistle-blowing is at work.

To see what was really going on we have to delve backwards into history in order to go forwards into clarity. And language is a major part of this confusion because today NASA prefers to refer to the ‘Apollo spacesuit’ as if it were an all-in-one item, but in the 1960s this was not the case. The patent filed by NASA for the Apollo suit clearly sets out the fact that the garments comprising the Apollo space suit were a collection of mix-and-match items designed to fulfil different functions. On a crewed Apollo mission the Command Module Pilot required a simpler configuration to that of the Lunar Module’s Commander and Pilot.

Figure 3. Order of suiting up and the usage of the several items that comprise the Apollo spacesuits – the terms ‘Donning’ and ’Doffing’ were adopted to describe the act of putting on and taking off spacesuit items

The above illustrations are from NASA’s March 1969 Apollo Mission Report. Note the pressure gloves and bubble helmet attached to the pressure garment. A pair of short-cuffed gloves and the white intra-vehicular cover complete the ‘in the CM assembly’. The CM’s white cover was less thick and had fewer connections than that of the LM astronauts. Their EVA visor helmet, worn over the pressure helmet, locked onto the outer rim of the pressure garment’s neck ring. The visor helmet and neck ring was protected by a covering made of the same protective material as the white EVA outer cover. The LM astronauts thicker outer cover was designed to protect them from the thermal and micrometeoroid conditions encountered during a lunar surface EVA.

The word ‘assembly’ as used by NASA in the above illustration describes the entirety of items required to create the pressure garment’s environment for an astronaut. However, NASA has an exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum (NASM) labeled PGA 076 which has a complete mix-up of the items from the CM and EVA modes. The identification states that this suit is the pressure garment assembly belonging to Neil Armstrong. But if you compare the items in the photograph (Figure 4) with those in Figure 3 above, you can see that the CWG (constant wear garment, top left) is not part of the CDR’s PGA, neither are the overshoes (bottom right) nor the glove/gauntlets that you see here – they belong to the protective outer covering, also shown.1

What you do not see is the actual pressure suit, which is supposedly lying within its white outer cover:

Figure 4. NASA S69-38889. Full pressure garment assembly worn by Armstrong, the inlet connectors on the chest are blue, the outlet connectors are red

Full references and data concerning the three modes of dress can be found in the Footnotes and in this paper we take it as said that the biomeds, sanitary wear and communication kits were standard for all three modes).2

Figure 4a. Due to successive failures in creating a viable Apollo spacesuit, a make-over of the whole spacesuit development program was undertaken in October 1964, and when failure occurred, new names proclaimed progress, or at least temporarily disguised the same old, same old. And as with military projects, changes to the management of the space suit project signified new code names.

So it came about that in November 1964 the PGA was re-named the Pressure Suit Assembly (PSA); its white protective cover garment worn inside the CM was renamed the IntraVehicular Cover Layer (IVCL); while the EVA white covering was called the Integrated Thermal and Meteoroid Garment (ITMG).3

Nowadays the term used is simply TMG. However back in 1964 the pressure suit cover was called the extravehicular thermal and meteoroid cover (coded ETMG) and consisted of separate pants and hooded jacket designed to be donned over the pressure suit at the start of the EVA. Held together through various suspenders and zippers, this two-piece 1964 ETMG (left, ILC Dover) was abandoned after the January 27 1967 CM fire had proven both Its design and its outer layer of Nomex to be not fit for purpose.

The two-piece ETMG was replaced in 1967 by an Integrated TMG – an all-in-one covering with improved anti-heat and micrometeoroid materials layered and stitched together throughout the covering. However, some prefer to interpret the use of ‘Integrated’ in International Latex Corporation (ILC) and NASA documents as meaning that the TMG cover and the pressure suit were literally attached together.

That the ILC’s use of the word ‘Integrated’ refers to the transition from the two-piece TMG through to the improved design of a one-piece TMG (without any openings for fire to get through to the pressure suit) is confirmed by the I/TMG on the label of Armstrong’s A5L white TMG.

Figure 4b. (ILC Dover) Neil Armstrong’s A5L Apollo training suit – multiple suit connection openings, Velcro and button snap attachments, arm and leg pockets, NASA emblem on the front left side – “Item Training I/TMG, Size A5L-009, Armstrong, Contract No. NAS9-10568” (Christies catalog)

Note the black rings that terminate at the points where the suit enjoins the wrist disconnects

Confused? You will be!

It might be more accurate to apply the ‘I’ to ‘Intra’ rather than to ‘Integrated’ because having nominated the CM Pilot’s gear as Intravehicular, both the CM and the EVA outfits were somewhat inaccurately called Extravehicular Mobility Units, EMUs. The CM could go outside the spacecraft in his TMG, but he was not all that mobile, being tethered to the CM life support systems by a cable known as the ‘umbilical’, and his TMG had fewer layers and therefore less protection than his colleagues. But the clothing confusion does not stop there: swapping Nomex for Teflon and losing its connectors, the design of the 1964 ETMG suit and pants combo remained within the Apollo program. Worn in a pressurized CM or LM, this was renamed ‘the coverall’ thereby inferring that this Teflon two piece was really a one piece.

Thereby c l a r i t y sank even further to the bottom of the Sea of Tranquillity.

Returning to the pressure garment itself, the US National Air and Space Museum (NASM) hasn’t kept up with this name change for the PGA, as we saw (in Figure 4). Nor indeed has NASA’s history website, as we will see.3 Moreover, the NASM has not bothered to educate the public concerning the precise evolution of the spacesuits used for the space race of the 1960 and 1970s. But then, even the manufacturers were unaware of some of the uses their suits have been put to.4

Biography of a 20th century Apollo

The only thing one really needs to know for the purposes of this investigation is how NASA got to the suits worn for the Apollo missions in general, and Apollo 11 in particular. The start of the US space suit research program had begun in the mid-1950s, but for the public it was the (1958-63) Mercury program which heralded the US space race and the three sections of the space projects Mercury, Gemini and Apollo were distinct episodes. This was not the case for NASA and its suit contractors. For them, the Apollo program was integral and sequential.

The astronauts on the Mercury program (1958-1963) had worn a pressure suit and a protective covering including a hard helmet, derived from the X-15 high altitude pilot’s gear, and these suits would only be pressurized in an emergency situation. This phase had facilitated the selection of suit contractors for the next phase. The Gemini program (1961-1966) and the Apollo program (1961-1975) operated together – both provided the events which enabled the refining of the hardware, as spacesuit engineers call their products. And during this period all problems had to be dealt with before the goal of a Moon landing by the end of 1969 could be achieved.5

In space suit terms Gemini suits were in development from 1963 and by September 1965 NASA was ready to order 14 A5L ‘training’ suits for Gemini from ILC Dover. These were followed by an order for 25 A6L ‘flight’ suits. The Apollo phase began with the tragedy of the January 27, 1967 fire on the launch pad. Out of which, like a phoenix from the ashes, the redesigned Apollo suit, the A7L was born. This iteration was used for Apollo 7 thru 14.

As ILC put it, “the A7L [sic] would combine the best of these iterations and produce the versatile system that supported launch and re-entry, vehicular activity and EVA.” (Those mix-and-match combos illustrated in Figure 3). Even so, this suit’s performance dictated further modifications. After two more research iterations (A8L and A9L ) the restructured A7L was designated for Apollo 15-17 as the A7LB. (Skylab also used modified A7LB suits, as did the ASTP). It had taken well over a decade to get there.

ILC also noted that:

The base AX5L to A7L configuration was “locked-in” in 1965, not because it was considered an ideal, but rather because it was the best at the time and the Apollo program had to progress to training and flight. The technical personnel intimate with the suit system recognized there were opportunities for improvement, especially in the areas of ease of donning, bending over and visibility [when] in the seated position.

Note that this comment does not specifically mention zippers, merely the means by which a person enters the suit – this will be noteworthy later. Also this comment does reflect the fact that the technological capacity of the materials they could use was not the only limitation to their creativity: the suit engineers were constrained by the size of the LM hatch and the amount of space within the CM. The CM and the LM in turn, were constrained in their own dimensions and weight by the amount of lift the Saturn V could produce. NASA was constrained by all of these criteria as well as budgets and time – the need to get the job done by 1969, come what may.

The rules of NASA speak

In order to decode the confusing language and acronym usage adopted by NASA for its suits, we need to understand three essential acronyms: the first acronym goes with the Constant Wear Garment (CWG). As seen in Figure 3, this short-sleeved long john (including socks) was worn next to the skin by the CMP under his pressure suit; and by all three crew members under that two-piece Teflon coverall worn in the ‘shirtsleeve’ environment of a pressurized cabin. In spacesuit terms the shirtsleeve environment is not related to temperature, but to the ability to move one’s arms freely – as opposed to the limited movement that a pressure suit imposes.

Figure 5. Buzz Aldrin inspecting the LM on July 18 1969 – essentially the original 1964 ETMG configuration, with different materials, wearing it in the LM is potentially misleading as these coveralls were not worn during the LM’s descent/ascent modes

The second acronym is for the Liquid Cooling Garment (LCG). In Figure 3 (the 1969 illustration) this long-sleeved front-fastening long john with socks (Velcro tabs on Apollo 11, zippers on Apollo 14) was worn next to the skin by the EVA crew, replacing the CWG.

The third acronym already dealt with, is the TMG, and we use it in this investigation to refer to the Thermal and Meteoroid Garment used for protecting the Apollo EVA pressure suit when on the lunar surface.

Here is the Apollo EVA suit with its portable backpack (PLSS) According to NASA data, this combo should support the astronaut for a maximum of 115 hours:

Figure 6. Apollo Extravehicular Mobility Unit with key elements marked – the reference A7L (the 7th iteration of the TMG) became the generalized appellation for Apollo suits up to and including Apollo 14

Technically and literally this EVA get-up is the only combination that can be correctly referred to as an Apollo Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU). However, as we have seen NASA is not fussy about mixing it up, and not knowing all the ins and outs of this Apollo garb, it has become general practise for many commentators more accustomed to the EMU used on the ISS to refer simply to ‘the Apollo suit’ as if it were all of a piece – albeit made up of numerous layers. And how many layers exactly varies across different sources. NASA’s very particular use of the English language means that the function of individual items is often misunderstood, and the elements of any particular suiting mode are then combined erroneously.

This lack of accuracy has not been controlled by NASA, rather it would appear to have been encouraged. After all, during the development of the elements required for the Apollo suits, it would have been simple and indeed necessary to keep the details updated and end up with an accurate record for all subsequent needs, whether media or technical, after the event. As this is not the case, (even the ILC Dover database has discrepancies when compared with the NASA photographic evidence, as we will see later) either these inconsistencies are due to carelessness – because it was not considered important, or something else was going on. The fact that NASA data sources lack clarity concerning Apollo 11 – THE mission – would tend to indicate that this continuing lack of consistency is deliberate. Whether these inconsistencies stem from a military imperative or are intended as a whistle-blow is debatable.

Swapping Whoppers

Taking the NASA history website as an example of these space suit shenanigans, the story of the Apollo suit is presented incorrectly in all respects: it informs us that on Apollo 11:

Two configurations of the PGA were worn on the Apollo 11 mission. The intravehicular configuration was worn by the Command Module Pilot (figure 2). The extravehicular configuration, shown in figure 3, was worn by the Commander and Lunar Module Pilot. The two configurations were similar in most respects. However, the intravehicular version was equipped with a lighter weight and less bulky cover layer and did not include hardware and controls necessary for extravehicular use.

By putting the pressure suit to the right of its cover suit, these NASA photos follow the tradition set up in the 1969 illustration (Figure 3) showing the donning sequence from the observer’s right to left. However, in every other respect, the above text and the captions to these photos are wrong. NASA’s figure 2 purports to be the CMP, Michael Collin’s intra vehicular configuration of the Pressure Garment Assembly. However, NASA captioned these suits as ‘Extravehicular’ and therefore it cannot belong to the Apollo 11 CM Pilot as stated in the accompanying text. The Apollo suit pictured in figure 2 on the NASA history site had nothing at all to do with the Apollo 11 mission. It is the next evolution of this suit, the A7LB (used for the Apollo 15 thru Apollo 17) and its zipper closures are in a completely different configuration to the A7L suit.

Figure 7. Incorrect mission, wrong suit – this is NASA’s figure 2 but captioned ‘Extravehicular configuration of the EMU’

And for further verification, the NASM holds on its website a photographic record, but not exhibited, labeled as the A5L 1965 developmental blue pressure suit used by Apollo 11 CM pilot Michael Collins. It looks nothing like the suit pictured on the NASA history website.

NASA’s figure 3 showing only the bubble helmet must surely be construed as the Intravehicular configuration of the EMU. If it were not for that completely wrong suit in their figure 2 one might assume that the captions on these NASA photos have been simply misplaced. But it is that wrong suit and the references to CMP in NASA’s figure 2 that demands that we look closer.

Figure 8. Correct mission, wrong suit – this is NASA’s figure 3 but captioned ‘Intravehicular configuration of the EMU’

Having ascertained that NASA’s figure 2 is totally wrong, and knowing that their figure 3 caption does show an Apollo 11 CDR and the LMP suit of some description, one might deduce that the figure 3 text is actually correct and this figure 3 is their A7L shown beside its A6L blue-and-orange EVA pressure suit (color version shown below):

Figure 9. If that were to be so, then the EVA visor helmet is not shown. But the Apollo 14 EVA helmet is shown with the Apollo CMP pilot’s gear in their Figure 2 – and he was never going to wear one! Again we are tempted to think that the captions are misplaced. But this mix-up can also lead us to think again about the differences between these two suits – and those helmets.

The helmets from the Mercury and Gemini programs also evolved over the period of the Apollo program. Over the years, NASA’s Langley spacesuit research centre carried out a lot of analysis of the suits and their accessories. Expert Jim McBarron states that the hard white shell of the protective helmet used during Gemini (which goes over the bubble helmet and protects the astronaut during launch/re-entry as well as supporting the EVA visors) was found to be inadequate during thermal vacuum (T/V) testing. It was changed to the red-colored Polycarbonate shell seen in NASA’s Apollo 9 pictures. He also tells us that this Extra Vehicular Visor Assembly (EVVA) also failed under T/V conditions – it deformed, draping over the bubble helmet.6

At the time there were no better materials available for constructing this protective outer helmet, the Apollo 9 red shell was retained, and for Apollo 11 it was simply covered with the complete TMG covering we see in the EVA photos. Jim McBarron states that the hard red shell is still there, you just can’t see it, and that was the best they could do. And with other changes relating to venting, the EVA helmet‘s disconnect ring was upgraded, resulting in a red anodized aluminum overlay onto the pressure suit’s blue anodized aluminum neck ring. As a result of that upgrade, all bubble helmets from Apollo 11 onwards would have their own red ring, the older blue ringed bubble helmets being retained for training purposes only. Which is why you see two colours on the neck ring in these photos, and why you see Armstrong’s exhibited bubble helmet with a red ring while he holds a blue-ringed bubble in an earlier photo (see Appendix 2).

Figure 10. Suit back uppermost showing helmet disconnect ring and open back flap with its zipper fastening

Each Apollo astronaut was issued with one training suit and one A7L flight suit. A second flight suit was kept in reserve in case anything happened to the primary flight suit. And indeed things did happen, some of the materials used in the suit construction had a shorter ‘shelf life’ than expected which then caused pressure leakage problems.6

For example, the time lapse between the scheduled Apollo 13 and 14 missions enabled the suit engineers to discover tears in the material used on the foot of the pressure garment. All the crew suits for Apollo 14 were changed out for new ones just weeks before the actual mission date. In the 2015 NASA technical presentation from which this detailed data emerges, a pertinent question was asked: what would be the effect if such a tear happened during a mission? Langley space suit analyst Jim McBarron first evaded the question but when asked again, said that the records did not show that there were any problems on the missions. This is the standard response from all those who can see perfectly well that there is a technical issue but still have to be seen to support the official Apollo data. But it is noteworthy that his response still didn’t answer the question, and when we get to zippers, you will see exactly why.6

Interestingly, all the Apollo suit technical data, including the pressure suit leakage data, was sent to the NASM along with the Apollo suits. The museum no longer has this data. Whether it was discarded, lost, or wrongly archived by the Smithsonian is not known. As the missing suit data reveals problems with pressure leakage during the Apollo experience, that’s not surprising. But it is part of a pattern: missing data concerning the technical aspects of these missions is inherent within the Apollo record.7

During a presentation of space suit gloves from the past to the present, NASA’s lead spacesuit glove engineer Amy Ross, now actively involved with the developing the lunar Artemis suit, was asked if there were lessons drawn from Apollo which informed future spacesuit design. Her reply was succinct:

Zippers are bad and cables are bad. During the Apollo moonwalks the metal braided cables [on the pressure suit and gloves] tended to fray and the zippers, which sealed air into the suits, got clogged with lunar regolith and didn’t work very well.8

The pressure suit zippers and metal braided torsion cables are precisely the two items most in evidence in those ‘spot the difference’ text, captions and photos on the NASA history website.5 You can imagine the consequences of the zippers fouling or jamming up before the Apollo 11 EVA.

Dealing with Zippers

The specialist zippers used on the Mercury and Gemini suits were very stiff and difficult to close, and there were problems with leakage from supposedly waterproof pressure zippers used earlier in the space program. Although the zippers adopted for Apollo were of a different order of magnitude – they were even stiffer and harder to close, as well as being liable to failure. Even so, having had a frank exchange of views over quality control with the supplier, B.F.Goodrich, (BFG) the Apollo A7L pressure suit zips continued to be used up until the end of Apollo 14.

The USSR took a different view. The Russian spacesuit developers had also ordered 50 of these pressure zippers from BFG – but finding them unfit for purpose they sent them all back to the USA.6

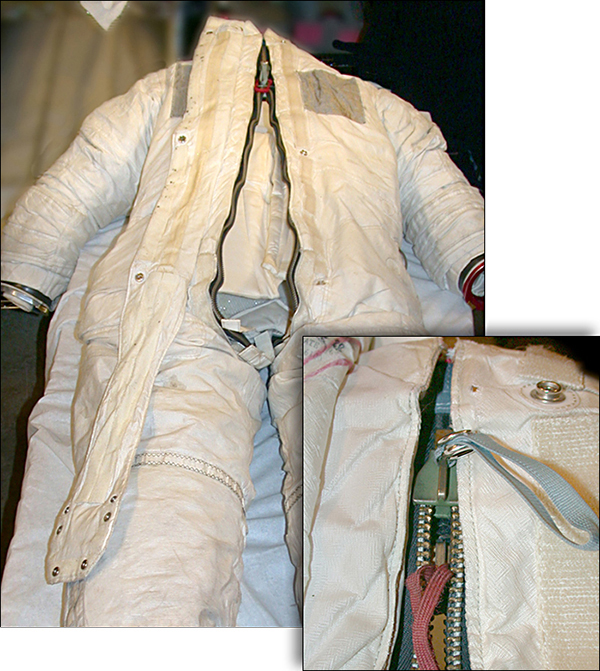

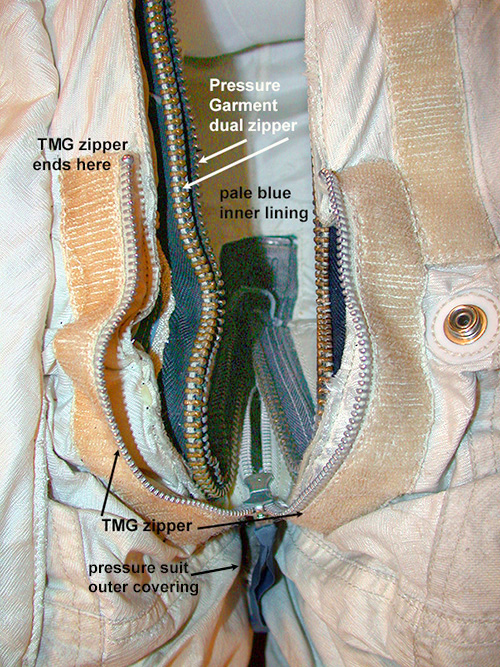

Figure 11. (ILC Dover) A7L pressure suit’s braided torsion cables across chest and shoulders and rear-entry zipper – which note, does not reach the neck disconnect ring

In 2017 Cathleen Lewis, a curator at the NASM Space History Department explained why this zipper has not been used by NASA since Apollo:

The type of zipper that was used relied on two heavy-duty, brass zippers that compressed a rubber gasket sandwiched between them when the suit was pressurized. While this seal was reliable, it did require frequent re-testing throughout the production and flight test cycle. The seal, while reliable for short-term use, was not so for long-term use. The chemical interaction between the copper in the brass zippers and the rubber gasket caused quick deterioration of the rubber (emphasis added).9

Figure 12. Details of the two sets of zippers sewn over each other – note the pale inner lining of the pressure suit and the dark blue outer covering of the pressure suit – we will come to the TMG zipper later

However, the Apollo missions are let off the hook because, as Cathleen Lewis explains:

As long as missions were less than a few weeks and required only a handful of re-pressurizations without retesting, then there was little concern.

By 2019 on the occasion of the restoration of Armstrong’s flight suit A7L Cathleen Lewis added this comment on the NASM website:

The zippers and synthetic rubber used on the Apollo spacesuits were only meant to have a shelf life of six months. As it was well known at the time, the rubber used in creating the pressure layer of the suits reacted quite negatively to copper.10

Which isn’t exactly so, ‘Quite negatively’ actually means that the rubber perished, and according to Langley’s expert Jim McBarron the safe period was four months, not six, and he was being generous. He also stated that the problem of perishing rubber was not well understood at the time – it was only because Apollo 14 had been postponed from its official start date that the aforementioned perishing rubber on the foot revealed itself. He added that it was only then that they worked out that all rubber trees produced a certain amount of copper. Although coming from the NASA field center in the business of analysing the spacesuit products – even that explanation sounds rather unlikely, and McBarron didn’t report it with much conviction.6

Neil Armstrong’s A7L flight suit’s pressure gloves have an ILC label CEI 2001A and delivery date 4/69 – so we should know that three months is the absolute safety window inferred by McBarron for his rotten rubber foot problems. But Cathy Lewis may well be correct – and the zipper problem was understood before the foot problem.

Back at At ILC Dover those A8L and A9L iterations were entirely dedicated to this rubber zipper deterioration problem. Coded aptly as the Omega Project various attempts were made to relocate the zipper on the Apollo pressure suit. Because, over and above the question of storage and passage of time between suit fabrication and deterioration of the vitally important sealing of the pressure suit, the loading of the astronaut’s reclining or seated body onto a vertical spine zipper configuration exacerbated any construction fault. As the Omega project is credited with the dates 1968-69, and the results of its research first used in 1971 on the A7LB for Apollo 15, clearly the A7L Apollo suits had shown up the problem. But that raises two further questions.

When exactly did the serious zipper problem first make news? ILC states that the Omega project was in the wind in 1967 after the end of Gemini and that infers that it was also a problem on the Gemini flights. Not only did they have the double rubber zipper on the pressure suit, these suits had a long black metal zipper down the back. How many accidents were there before this 1968 revelation? And if it took until 1971 before a reasonable alternative was produced, what about Apollo? Do you send an astronaut out beyond LEO for an EVA in a pressure suit at or near its sell by/use by date? Or, back in 1968 do you realise that given the limitations of the technology these problems are insurmountable – and resort to simulations to represent the stated events.

If the decade allocated to the Apollo program was useful from an R&D point of view regarding development of the suits, thus far, by all accounts, this suit was not coping with all the demands placed upon it. For the pressure zipper issue, the change over to the A7LB diagonal zipper configuration removed some of that problem, as did changing the manufacturer of the zipper itself but it didn’t answer another. That of dust and dirt penetration into the suit. .Dealing with the front of the suit first, the Apollo A7L EVA suit had an additional TMG cover which went over the chest and was used to avoid dust contamination of the various connectors and wires. To peel it off you pulled at the NASA logo. In the picture below you can see these covers are worn by Armstrong and Aldrin:

Figure 13. Publicity photo: Apollo 11 crew, ‘This is what we are going to look like when on the Moon’ – note two early blue disconnect neck rings and a partial red overlay on Aldrin’s neck ring, plus the reflective gold visors on the EVA helmets

The above PR image was taken before the mission badge was sewn on and all these suits are looking squashy because seated under the studio lights they wouldn’t be wearing an inflated pressure suit underneath. Or even any pressure suit at all, since the mix-and-match wardrobe items enabled a costume to be accessorized expressly for studio photographic sessions – and any training simulations where learning a task was initially facilitated by not wearing the pressure suit.

Both practises would legitimize the very invention of a stage costume. Note that Collins holds a bubble helmet, since he will never be going outside the CM, while CDR Armstrong and LMP Aldrin hold their visor helmets. Note the contrasting color of the beige Velcro on their sleeves, just above the wrist, this is to take a protective cover patch of TM material over that plug on their arm. Then note the complete absence of Velcro tabs on the front of the CDR and LMP pilot’s suits. This is because they were wearing the protective TM covering designed for the front of their suits.

Now compare the Moon background PR image with with the LM background PR image below:

Figure 14. Apollo 11 astronauts photographed in front of a LM, again with blue disconnect neck rings

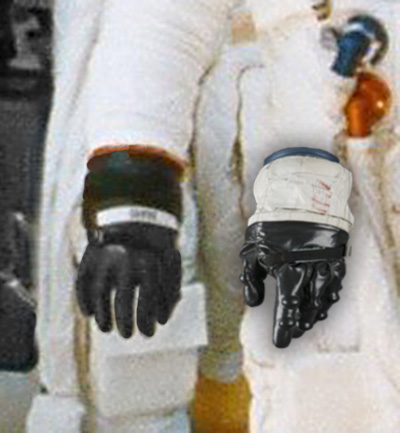

Here you can also see white LCG cuffs emerging from the two EVA suits. And note that the red and blue rings on all these cover suits, to which gloves should connect, are up the forearm – not at the wrist itself. Some commentators assert that all the astronauts wore comfort wristbands to stop these aluminum rings chafing. Sounds reasonable for training purposes on Earth, but when the suit was worn with its pressure garment, that is hardly a problem.

It is also said that soft comfort gloves were worn under gloves of any description. There are no traces of either item on the picture of Armstrong’s PGA 076 gear (Figure 4). Nor on the 2019 illustrations of the Apollo 11 mission. But there is a photo of Armstrong in the prep room at NASA before the launch wearing a pair of white gloves before donning his pressure gloves – and we also see his wedding ring. One may wonder how a ring was permitted under a pressurized glove.

Figure 15. Armstrong in the prep room – note the red disconnect ring, stitched-on mission badge – and lack of dust cover

Covering up for the exposure

One can also see in Figure 14 that Collins had fewer front connectors than Armstrong and Aldrin. Notice how bulky the two EVA suits look, especially across the shoulders, with Armstrong and Aldrin doing very good impressions of the Michelin Man. Then compare the picture with any of the lunar surface photos – all of which feature astronauts wearing white costumes looking more like Collins does in Figure 14 – no bulking up, no LCG, and consequently no pressure suit. And note that Armstrong and Aldrin, supposedly practicing lunar surface EVA tasks, were not wearing the protective TMG cover on the front of their suits. Instead we see the horseshoe shape made by the Velcro tabs to which it should attach. But they are now wearing the TMG patches on their arms.

Figure 14 is the complete inverse of the Moon publicity photo in Figure 13. And that also goes for the demeanour of the three astronauts. In the Moon publicity shot the two EVA crew are smiling, but the CSM pilot is not. In Figure 14 Collins is smiling slightly but only with his mouth and the other two are looking very serious, even sad. The presence of Collins in front of the LM is another anomaly. Since he was never going to be on the surface why is he even in this training photo – unless it is to emphasise the contrast. These two photos look like a deliberate game of ‘spot the difference’ and a subtle whistle-blow alerting the observer to yet another aspect of what is completely wrong with the Apollo record.

So let’s go back to this Velcro tab issue, why obsess about such a tiny detail? Because of the dreaded lunar dust, that’s why. The lunar surface dust debate was in full swing during the 1960s. No one knew for sure what the conditions would be like at the Apollo 11 landing site, how deep the dust would be and what effect it would have on the lunar EVA equipment and personnel. In the highly unlikely event that it was decided not to use the covers before leaving on this very first landing, why have them on in the publicity shot and in the PR videos? This front TM protective cover was never used on Apollo 11, nor on any other mission. The Velcro tabs to which it should be applied can be seen in all the lunar EVA photographs.

Figure 16. NASA Apollo 11 illustration shows the connector cover and has the EVA gauntlets extending to just below the inner elbow crease – in the Apollo 11 photos this is clearly NOT the case for either item

A lot of fuss was also made about the amount of dust expected at the other designated landing sites, surely protective TMG covers would be worn, wouldn’t they? No. All the training suits were issued with them (Cernan’s Apollo 17 is documented) but after Apollo 11 every mission was photographed somewhat differently: both the publicity shot and the EVA shots would feature TMGs with no front dust covers. Which infers that the lack of dust covers on the Apollo 11 EVA images meant that every subsequent mission had to conform to the same regimen as that Apollo 11 LM training scenario: TMG patches on the arms but not on the front.

From a certain perspective that makes the fuss about the dust another potential blow on that whistle. That these protective TMG front flaps were deemed unnecessary on the very first lunar landing is a nonsense while their absence tells us that either the lunar dust was not exactly as anticipated. Or the Apollo 11 TV coverage and the lunar surface images were taken during photo studio sessions Earth. Which might help the Hasselblad expert Jan Lundberg who couldn’t explain why Buzz Aldrin was standing in a pool of light and recommended that Armstrong explain it. The lunar EVA images stand for the explanation.7

Figure 16a. (ILC Dover) Armstrong’s dust cover, December 1968. This cover was initially intended to prevent lunar dust from gathering around and jamming the connectors. The front flap allowed access to the space suit purge value. Two curved side openings allowed oxygen hoses to slide under the cover – Item I/TMG Connector Cover, Part No. A7L-201109-01, Size Armstrong, Serial No. 063, Date 12.68, Contract No. NAS 9-6100 (Bonhams catalog)

Misnomer Murders

The TMG cover exposure raises other questions as to the apparent difficulties of dealing with lunar dust, notwithstanding the everlasting grumble about dust making the suits dirty (and therefore less reflective of the sunlight – the reason they were white in the first place). In 2006 NASA published a document about the Apollo experience in which there was much discussion as to the dust at various sites analysed with a view to future crewed lunar landings.11

In 2015 Langley’s expert Jim McBarron was asked how they had ascertained the dangers of the dust, when no one had been to the Moon. He responded that based on their expertise, geologists had made up artificial lunar dust, which they had sprayed onto the suit materials to test their abilities to withstand abrasion and penetration. Perhaps inadvertently supporting the ‘We didn’t go…there’ school of thought, he also told his audience of present-day space suit engineers that he had seen the suits come back from the missions – and they didn’t look a lot different to their own test samples. Nor in his opinion did the dust effects vary much from mission to mission.

His audience fell silent – likely remembering other NASA documents which state that they had to wait for rocks to be brought back from the Moon by Apollo 11 before being able to create artificial lunar dust.6 Again, present day engineers are having to rely on data that does not necessarily reflect the circumstances as accurately as they might wish. Nevertheless the 2006 dust document is worth reading just for the contradictions within its pages.

Fig 16b. Close up from AS11-40-5942 (39 shots after the famous Aldrin picture AS11-40-5903) – note Aldrin’s right glove with exposed black ring and the build up of dust and dirt on his forearm and on his cuff

Thirteen years later in 2019, when it is asserted that the lunar dust clogged up zippers and penetrated the outer layers of the TMG, even more serious questions are raised. The seal of the TMG and the pressure suit zippers were largely covered by the PLSS. If dust had truly managed to penetrate their backs, then all the more reason to be wearing their frontal dust covers. However, Jim McBarron had stated that “they did everything by analysis”. Deliberately testing the zippers and the TMG materials as separate items at NASA test facilities would produce such results – along with that report’s sentence construction. Given the architecture of these two garments, the sentence should have read, “lunar dust penetrated the outer layers of the TMG and clogged up [the pressure] zippers”.

Then again, being delightfully vague about the zippers might have something to do with managing a serious problem visible on the Apollo suit displays at the NASM, thanks to this 2019 statement. We are informed that:

“The ‘zipper’ is actually a misnomer in that the A7L back entry was through two zippers sewn over each other.” So far so good. “The inner zipper had rubber teeth and provided sealing. The outer (externally visible) zipper was a conventional metal-toothed slider for mechanical restraint.” Not so good, and an incorrect description of the pressure zipper which as we recall was in fact:

Two heavy-duty, brass zippers that compressed a rubber gasket sandwiched between them when the suit was pressurized.

The 2019 zipper statement comes with the warning ‘citation needed’. We should say so! This is again inferring that the suit is a one-piece suit. Associating the inner zipper with rubber leads the reader is to assume that is the pressure zipper, and conclude therefore that the metal zipper is the white zipper stitched onto the crotch of the white TMG cover seen in Figure 12.

Neither the CM TMG suits nor the EVA TMG were able to retain pressure, and the donning instructions for the A7L does not include this white zipper.10 Nor do the recent 3D scans of an A7L at the NASM show any white zipper. NASA issued step-by-step instructions to its astronauts as to how to do up the two pressure suit zippers (a big palaver using two different lanyards) and then how to close the outer white TMG flap over his spine, and then through the crotch, keeping it in place with the Velcro and stud fastenings. NO white metal zipper!

So to be clear: the two pressure suit zippers were sewn over each other, providing a double layer of protection against a loss of pressure BUT the two garments – the TMG and the pressure suit – were NOT sewn together to form one suit.

Figure 17. Back view of the A7L TMG showing the fold-over flap, the pressure studs and Velcro tabs to hold it in place over the pressure suit. The pressure suit’s double zippers are visible – (the silver rectangle of anti-abrasion metallic Chromel-R on the upper back was designed to offset any bouncing or abrasion from the PLSS)

Figure 18. Inserting a pressure suit into a white outer TMG at ILC Dover – a scene from a US National Archives 1970 film12

Neither protective covering alone, whether the CM suits or the EVA white covers were able to retain pressure.The red helmet disconnect ring belongs uniquely to the pressure suit, and it cannot seal to the white suit as it only closes with a flap. Moreover, the seals/connections on the visor helmet do not compress, they have a door latch tongue design purely to facilitate quick attachment to the pressure suit’s outer red collar, see Figure 19:

Figure 19. Armstrong’s TMG – clearly showing how the fabric TMG sits against the pressure suit disconnect ring

To zip it up: any white TMG suit equipped with a white crotch zipper is not a flight suit, rather as already stated, it was a costume accessorized as required for photo/film studio shoots and simulations. As such, the astronaut didn’t need to wear a pressure suit, nor the unpleasant nappy/condom affair. But he did need to be able to go to the washroom without taking off his costume, which had a neck ring fixed to it, simulating the pressure suit neck ring.

So a crotch zipper is just the ticket. The Wikiwand contribution to the zipper discussions looks to be an effort to justify the short white zipper seen in photos of Ed Mitchell’s Apollo 14 suit – but when taken together with the new NASM 3D scans of Al Shepard’s Apollo 14 suit, sounds more like a whistle blow.

Braided Beams

The other takeaway from the Apollo suits mentioned by Amy Ross is that the braided torsion cables associated with the pressure suit and gloves frayed very badly. Below is a side view where you can see how the braided cables extended over the back of the shoulders, how inflated the torso and thigh region is – and that the astronaut cannot reach the ground to pick up anything he might drop – such as a hammer.

Figure 20. St. Valentine’s day testing of the A6L International Latex Corporation, 1967 test (ILC Dover)

According to the reports from NASA, all these tension cables became very frayed. Again this sounds rather unlikely, when the longest amount of time scheduled to be spent on the lunar surface and not all at work, was of just over three days (Apollo 17) – but it would be entirely commensurate with months of systems analysis and training on Earth, including any photography and filming done for such purposes.

Figure 21. This is a larger picture of the Apollo A6L EVA pressure suit (ILC Dover)

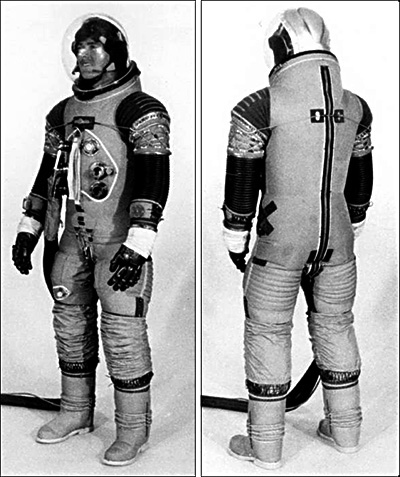

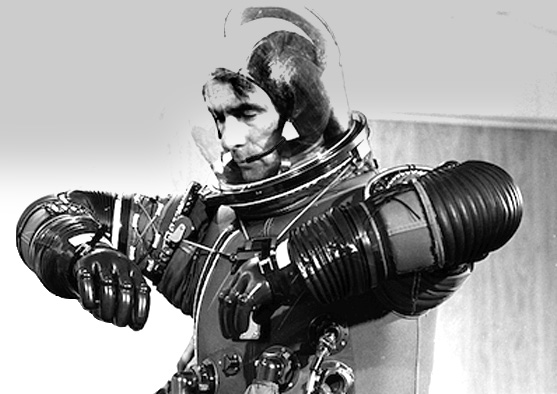

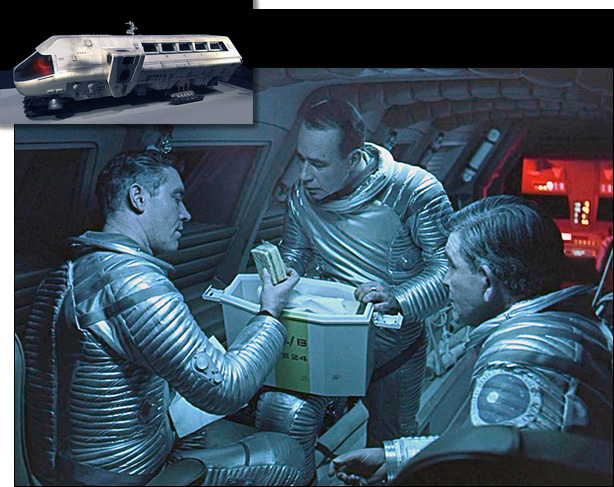

Below is the A6L pressure suit’s shoulder torsion cables being tested by ILC Dover’s primary astronaut test subject Tom Sylvester. This image strongly recalls the similarly-designed ribbed suits from scenes in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey:

Figure 22. Testing a pressure suit’s torsion cables (ILC Dover)

During preparations for his ground-breaking film Stanley Kubrick had NASA Apollo spacesuits hanging in the production offices at the Borehamwood studios, UK. The name of the actor who played Heywood Floyd in 2001 was William Sylvester, while the ILC Contract End Item (CEI reference) for Apollo items (seen on Borman’s glove and Armstrong’s dust cover) was 2001 A (see also Links to the Films of Stanley Kubrick):

Figure 23. Ribbed space suits worn in the Moon bus – a scene from 2001: A Space Odyssey (MGM 1968)

The astronauts are discussing the merits of the sandwich filling: Floyd says, “What’s that, chicken?” Bill responds, “Something like that, tastes the same anyway.” The sandwich with its five layers is analog to A5L sandwich! They are in a Moon bus with five-a-side windows. We see the airlock entryway and it’s pressurized because they have removed their helmets and their gloves. Which is where we come upon another set of anomalies.

Hand in Glove

The Apollo A7L glove sequence set out in 1969 was intended to be as follows. The astronaut could, if he so desired, don a pair of white comfort gloves – before putting on the pressure glove and matching its colored connector to the color-coded forearm ring of the A6L pressure suit.8

Red on the right and blue on the left.

If remaining in the CM a restraint glove made of protective materials went over this pressure glove. For an EVA, before going out onto the lunar surface a different glove with a much longer gauntlet cuff, reaching nearly to the elbow, was worn.

So let’s look closer at the gloves used on Apollo, these were also an evolutionary design process which went from the very early gloves used by the X-15 pilots (such as Armstrong) through the Mercury and Gemini programs to the Apollo EVA astronauts (also, such as Armstrong).

Therefore the timeline for the gloves now being developed doesn’t differ significantly from that used by Apollo.

Figure 24. Timeline for typical glove production today. Here indicated by L-18 thru to L=Launch. NASA expert Amy Ross says that this timeline is the same pattern as that of Apollo, and even today a customised hand mold would have to be made 18 months prior to launch

PVU/FC is the first try-on and agreement by astronaut for fit. TRNG/GLV is a training glove. FLT GLV ATP is astronaut approval of his CM in flight glove. TMG ATP is approval for his thermal and meteoroid gauntlet. The training glove delivery date of nine months prior to launch concurred with the November 1968 date on the ILC label inside Armstrong’s suit at the NASM is another indication that this suit is his training suit – not his flight suit. However, creating more distance from Apollo, the former numerical development references of the gloves changed after the 403 series to references designated by Phases with Roman numerals, thereby creating more distance from Apollo. The current Phase VI (six) is the inverse of the Roman numeral IV (four) and NASA’s abbreviation of IV for IntraVehicular adds yet another layer of potential confusion for the general public.

The pressure glove used on Apollo evolved through two iterations in 1962 and 1963 providing the basis for all NASA pressure gloves until 1978. The pressure glove’s suit disconnects would be in proportion to the usage put on the suit. The Apollo 3.75 psi pressure suit hasn’t been considered useful for any space operation since Apollo. And even though they look relatively flimsy, the glove disconnects were difficult to fasten, requiring a two-step rotation and locking process after insertion to help ensure minimum loss of pressure.

Figure 25. Wrist disconnect rings with locking positions between the arm and the glove/gauntlet

Compare the above with what is now considered necessary for a lunar EVA: the new ARTEMIS suit and glove connectors are going to have to cope with a pressure of some 8.0 psi, which requires a hefty articulated metal wrist connector. As for that longer EVA glove, the manufacturer had stipulated that the “outer thermal glove extended well back over the IV glove – TLSA juncture”.

Which means that inside the CM all the Apollo astronauts wore a shorter glove made of fewer layers of protective material, and that this glove only reached as far the aluminum connectors to the pressure suit. When outside the spacecraft on an EVA, the outer protective glove had to completely cover the pressure suit aluminum wrist connectors and it went much further up the forearm, as seen in early NASA illustrations – but interestingly, not in the Apollo lunar EVA photographs.

For the apparel oft proclaims the man

For the apparel oft proclaims the man

And therein lies the tale. It is in the small details, the order of dressing and details such as the color of helmet rings, boots and gloves, together with their fixings which inform the observer that all is not as it seems. It is on the record not least by Neil Armstrong, that the Apollo 11 EVA suit required two distinct phases of dressing and this principle has been maintained as correct procedure over the years, even when reporting the Apollo 11 mission 25 years after the event. With visions of already fairly adrenalin-fueled men struggling in the tight space of the CM to achieve what required several helpers back on Earth, we are informed that the Apollo 11 moonwalkers were to don their LCG and pressure suits in the CM before accessing the LM and descending to the lunar surface.

Then, according to Harrison Schmitt (Apollo 17) and author Peter Bond, the Apollo 11 astronauts in the even tighter space of the LM and prior to emerging for their EVA, would add their TMG covers along with the lunar overshoes, the protective outer gloves, the visor helmets and the PLSS systems. Assuming Schmitt actually read the book for which he wrote the introduction, one would wonder.13 Even though we have seen that there is no question of the TMG being an ‘all-in-one pressure suit’ and that the black pressure gloves had to connect and lock to the pressure suit worn under the outer white protective cover, surely they would have put on their TMG covers prior to descending to the lunar surface, in case the LM failed them. This clear difference sounds like another toot on the whistle.

Figure 27. The Apollo 11 July 16 1969 walkout to the Saturn V – note the yellow-rimmed overshoes protecting the pressure boots, the black pressure gloves attached to the red and blue rings belonging to the hidden pressure garment and the different number of connectors on the EVA and CM TMG suits

Here is another shot from the end of the Apollo era showing the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) walk out in 1975. As an aside: space and weight were important considerations, these yellow overshoes seemingly appear only at walkouts. Perhaps they were retained by the launch crew once the astronauts were installed – or this color had a hidden Apollo solar symbolism relevant only to those in the know. And in that context, there are several occult meanings to be derived from the change of color to the blue lunar overshoes and to the combination of blue and yellow. As is the fact that the ridges on the lunar overshoe were designed to match the ridges of the LM ladder. Ostensibly very practical, that there were nine ridges on both shoe and ladder likely had other meanings for those in the know. Not least that the astronauts recruited after the Mercury Seven for the Apollo phase called themselves the Next Nine.

Figure 28. Image 75PC-409 ASTP – walkout to the rocket in 1975 shows the black pressurized gloves attached to the pressure suit – and not connected to the outer white cover

And in the close up view below, the pressurized black glove is shown again next an un-pressurized black glove with its ‘bubble knuckles’, which of course disappear when it is pressurized:

Figure 29. Close-up from 75PC-409 with pressurized glove (left) and a comparison glove un pressurized (right) – the black cuff is the ASTP glove while the white cuff is an Apollo glove

This above all: to thine ownself be true,

The display at the National Air and Space Museum, in trying to be all things to all men, suggests the requirement for people to forget the number of individual items that constituted the astronaut’s EVA garments and instead accept that the aggregate layers constitute the pressure suit. As any fire fighter or deep sea diver will tell you, this is not how it works. But such thinking does go a long way towards explaining other remedial actions such as the change of names from PGA to PSA.

To further mitigate any unpleasant revelations, the public have been informed, ad infinitum, that the bubble knuckle pressure gloves (Figure 29) were worn in the CM and that the TMG’s EVA gauntlet glove contained an integrated pressure glove. Displaying this gauntlet next to the TMG of this so-called PGA assembly (below) would inform the uninitiated that these EVA glove/gauntlets connected and locked to the TMG itself.

Figure 30. (S69-38889 adaptation by Jim McBarron) A7L pressure garment assembly

It’s hard not to conclude that an authority is fire-fighting the problems associated with all the anomalous Apollo 11 photographs.

For the more charitably inclined, confusing the public as to the exact functions of the Apollo suit can be seen as:

- A lack of knowledge on the part of the curators at the NASM due to

- A lack of communication between NASA and the NASM.

For the less charitably inclined these muddles are due to:

- A creative decision to assemble attractive displays for the public with little regard for the reality, due to

- The imperative of supporting the evidence displayed in the Apollo EVA photographs.

And it must follow, as the night the day,

that there is another option. For the ever hopeful that real progress can be made in crewed space flight this side of the 21st century, the anomalies presented across the Apollo record (including those muddles on the NASA history website, uncorrected to this day) are whistle-blowing. Discontinuities across the various technical aspects of the mission records that went unnoticed at the time are evidence that these were very subtly seeded within the Apollo program by ‘the good guys’. Seeding intended for the future – when technology and an emotional distance from the events of the 1960s would permit those outside the space program to discover for themselves the true origins of the Apollo project.

The constraints imposed on 1960s technology by the physics of the natural world and how those issues, not so much the political spectrum, were the real reason that the Apollo program unfolded as it did – a decision of the few to fake what you can’t make happen – led to all the Apollo anomalies we are able to now discern. At the time these were discreetly seeded by the many who understood that freeing space exploration from the historical burden of Apollo would enable space engineers of the future, without losing face, to take a different tack altogether from that chosen by the Apollo decision makers.

That future is now, and it would seem that contemporaneous whistle-blowing is continuing today. Although it would be also fair to say that if the muddles we are seeing with the NASA organisations are simply a disconnect between past and future generations of space engineers, the result is the same: it can be seen that the Apollo record does not stack up.

Thou canst not then be false to any man.

Despite the fact that the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal boasts part of a 16mm frame of an astronaut standing in full sunlight with his protective sun visor/sunshades up, and says it is Neil, when it comes to exactly who these whistle-blowers were, you cannot assume it is always the ‘man in the suit’. It is the aggregate of details and circumstances that create a spike on the sound chart and not a single person. As is well known, the American researcher Bart Sibrel asked most of the Apollo astronauts about the authenticity of their lunar trip – and has been thumped by Buzz Aldrin for his pains. On one occasion however, when he asked Buzz more of the same, he was given the impression that the Apollo 11 astronauts were simply doing what they were told. As Buzz had famously replied:

“Well, you’re talking to the wrong guy! Why don’t you talk to the administrator at NASA! We’re passengers! We’re guys going on a flight!”

So in all of this discussion concerning perceived space suit shenanigans, it is important to bear in mind the heinous position of the astronauts, especially when reading the next section on the Apollo 11 gloves/gauntlet/cuffs. The photographs discussed below necessarily involve Aldrin, but just because he is wearing them, does not mean that he shares our analysis of these photos; nor is he necessarily the instigator of a whistle-blow. All the photos for the Apollo 11 shoot were conceived and designed in advance of the mission dates and whether in the know or not, since he or his stand in, living or simulated, was dressed and set in place for the photography and filming according to the directions given by the director along with the producer and indeed the full team, he was to some extent, both actor and passenger.

Imagine you’re tooling around on the surface of the moon and your Rover Car breaks down. What do you do? Walk back to the Lander? Imagine the consumables you use in that mile walk? Things do break down. That Rover Car on the moon is a huge red flag that says fraud and hoax. The goofy idea that the astronots would drive around on the moon’s surface in a car they take to the moon screams PR hype. Anyone who contemplates driving on back roads on earth know of the lethal dangers involved. Driving on the moon? Sure, no big deal…just call AAA…lol.

Merry Christmas to the Peanut Gallery. This one was a little tough to read through since I already know NASA is one gigantic fraud and no one was more programed to believe the fantasy than me. I had an engineering professor named Frank Groat who taught statics, dynamics and strength of materials. He claimed to have worked on the parachute system for splash down at NASA. I had no reason to doubt Frank but if I could travel back in time to the early 80s, I would ask Frank the following: So let’s say you were lucky enough to fly three dudes back and fourth to the Moon. Why risk drowning them? Why not just land in Kansas? Or if water was a must do, how about the Great Salt Lake? Just for the extra buoyancy…Maybe Lake Okeechobee. No one is going to die of hypothermia there. Just to hear what Frank would say, since he had no reason to doubt NASA was legit, he did his little part with a slide rule and a pocket protector with mechanical pencils.

Then there’s my Engineer friend that worked on the Space Shuttle’s life support system for over a decade and he was recruited fresh out of college. I have never asked him if he doubts the idea that NASA’s a legit thing. My guess is even if he had doubts, so much of his identity is wrapped up in being a former NASA Engineer that there’s zero upside to publicly or even privately expressing doubt. Who on Earth would want to admit to being party to the greatest fraud in history?

You can see why I would have no reason to doubt NASA was legit knowing the Professor and the Engineer, on top of the life long programing. But I do remember looking at the world atlas as a child and seeing the solar system model of planets revolving around the sun and thinking ‘this can’t be real’ … as an 8 year old! They went too far with the fantasy when they took the car to the Moon. Thinking about the logistics and nastiness of simple body functions for days in space without a shower and the stench of body odor in a tin can. Insert a GIF of Colonel Kurtz saying “the horror, the horror’ comes to mind as incredibly appropriate.

Here’s the link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VKcAYMb5uk4 that drills down to how horrible it would be in a tin can with 2 other men without a toilet or shower for several days “The horror, the horror”