Jonas Alexis and Jim Fetzer

This marks the final phase of our exchange, and I will address as many questions as possible that relate to the topic at hand. First, I would like to express my appreciation again for the opportunity to engage in this discussion with Fetzer. That said, I am somewhat surprised by several points of mischaracterization in his most recent response, perhaps unintentional. For instance, he writes: “Rather inappropriately, however, he claims that I beg the question by presuming that Roe v. Wade was correctly ruled (though now returned to the states and creating a patchwork quilt of laws and statutes governing abortion), as though I were using Roe as a premise of my argument.”

I never asserted that Fetzer was using Roe as a premise in his reasoning. I made it clear that “Fetzer repeatedly invokes Roe v. Wade in support of his thesis—both in the article under discussion and in his book Render unto Darwin.” I was careful to note that he supports his argument by appealing to Roe, not by presupposing it as a premise. Thus, his characterization is inaccurate. Moreover, it is historically untenable to suggest that Roe “emerges as the conclusion of a thorough and systematic review of relevant considerations,” given the numerous historical examples I have already provided.

We can take the argument even further by noting that the Supreme Court has, on numerous occasions, been demonstrably wrong in matters of grave moral and constitutional significance. For instance, Fetzer would hardly maintain that the Court was correct in Korematsu v. United States (1944), the decision that sanctioned the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. For readers unfamiliar with this case, it involved the forced relocation and incarceration of hundreds of thousands of individuals of Japanese descent in what have been aptly described as concentration camps. Notably, two-thirds of those interned were already citizens of the United States![1]

This policy was implemented under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who faced substantial domestic opposition to U.S. involvement in World War II. At the time, public opinion strongly favored non-intervention, and Roosevelt’s administration sought strategies to shift that sentiment in favor of engagement. Certain actions by officials within the Roosevelt administration, including those involving Jewish figures such as Harry Dexter White, contributed to escalating tensions with Japan in the months leading up to Pearl Harbor.[2] As the late historian Thomas Fleming observed, Roosevelt “had seduced America into the war with clever tricks, one-step-forward one-step-back double-talk, and the last resort provocation of Japan. Deceit had been at the heart of the process.”[3] Roosevelt might not have resorted to those “clever tricks” had he not faced mounting pressure from both the World Jewish Congress and Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr., who was Jewish. Fleming suggests that Roosevelt appeared to fear Rabbi Stephen Wise and Henry Morgenthau Jr. Even the State Department recognized that there was “a wild rumor inspired by Jewish fears” circulating within the Roosevelt administration.[4]

Fleming moves on to say:

“Pressured by his Jewish secretary of treasury, Henry Morgenthau Jr., Roosevelt met for a half-hour with Wise and other Jewish leaders. In a typical fashion, when he was faced with the topic that he wished to evade or avoid, FDR spent most of the time talking about other things and finally confessed he had no idea how to stop the slaughter. All he could offer was another statement condemning the Nazis in general terms and warning them of postwar retribution.”[5]

The narrative does not conclude there. Again, Roosevelt’s “attempts to skirt the Bill of Rights and pressure his attorney general into silencing the Jew-baiting loudmouths of the lunatic fringe in court were evidence that this problem loomed large in his mind.”[6]

In other words, political and elite figures such as Roosevelt were able to circumvent both the law and the will of the majority, constructing a moral fiction to justify their actions. The Supreme Court effectively legitimized this behavior, granting them the authority to act beyond constitutional restraint. This was neither the first nor the last instance in which such overreach occurred.

In 1927, in Buck v. Bell, the Supreme Court once again granted the elite a legal sanction to impose their will—this time by authorizing the sterilization of individuals deemed unfit to reproduce. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. infamously declared, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” Fetzer, of course, opposes all such Supreme Court rulings that reflect moral and judicial corruption. The only decision he embraces—or invokes to justify his position—is the Court’s endorsement of abortion. But why the selective reasoning? Why not appeal to Buck v. Bell? Why not to Korematsu v. United States? Or to Bowers v. Hardwick, in which the Court criminalized consensual homosexual conduct? Fetzer, naturally, would reject any of these as moral precedents. Yet, when the Supreme Court upholds abortion, he insists that such a ruling must be accepted as morally sound.

In short, the Supreme Court, to a considerable extent, has historically ratified the will of the elite and provided ideological justification for their agenda. This raises a fundamental question: did the Court conduct thorough research in reaching such decisions, or is it possible that it was profoundly mistaken? And if the Court was indeed wrong on such a central issue, can we find historical evidence that it similarly served elite interests in the matter of abortion? As demonstrated in the previous analysis, the answer is a resounding yes. If Fetzer insists on supporting his thesis by appealing to Supreme Court authority, then consistency would demand that he also accept Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the decision that overturned Roe v. Wade. Will he uphold the Court’s judgment in that case as well?

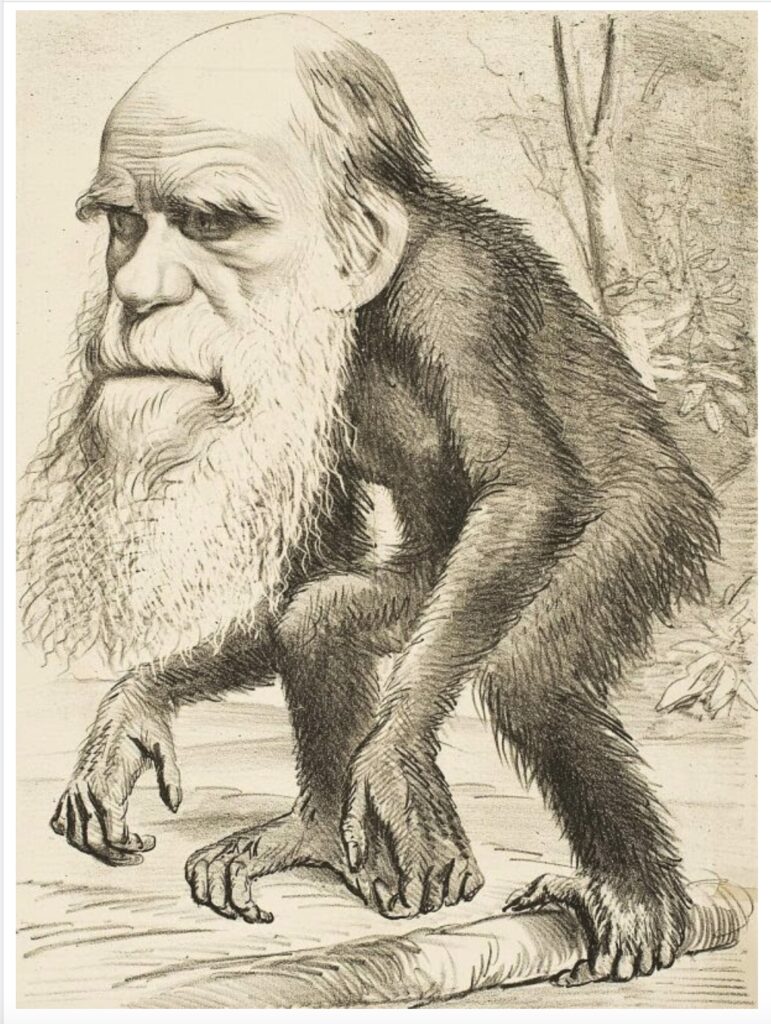

Fetzer Says Farewell to Darwinian Morality

I am pleased that Fetzer acknowledges he does not align himself with the Darwinian fraternity in matters of morality—meaning that he would not endorse Kevin MacDonald’s exhortation, in Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition, for readers to adopt a Darwinian framework. My concern, however, is that Fetzer fails to address these crucial issues in Render Unto Darwin. Setting aside the so-called Christian Right, the central problem with Darwinism has always been its inability to correspond with the moral realities of the world. This fundamental disjunction is precisely why, from the very beginning, many thinkers have raised profound objections to it, including Friedrich Nietzsche himself.

Fetzer and I concur that objective morality “elevates the human species above all others,” and that certain groups—such as Israeli Zionists—have forsaken their moral potential by perpetrating acts of genocide against the Palestinians in order to seize their land. In this respect, we stand in agreement with Fetzer. Yet the crucial point remains that the Darwinian framework categorically denies the existence of objective morality, thereby placing Fetzer in a philosophically untenable position within the Darwinian fraternity. In this sense, he becomes something of an intellectual outlier, if not an outright dissident, among his Darwinian peers.

In his initial response, Fetzer sought to attribute many of the major wars in modern history—including the Bolshevik Revolution—to religion. However, when I demonstrated that this claim is historically unsustainable, and when I cited scholarly literature showing that the ideological foundation of the Bolshevik movement was atheism rather than religion—and that this same ideological current later evolved into Maoism and unleashed vast bloodshed across Asia—Fetzer offered no substantive reply. Instead, he abruptly dropped the accusation and shifted the focus to the Old Testament, asserting that “combining the Old Testament (featuring a God of vengeance and retribution, where genocide abounds) with the New (featuring a God of compassion and love) into a single volume may have been the gravest intellectual atrocity of world history.”

Thus, the problem is no longer religion per se, but specifically the Old Testament. What a rhetorical pivot! At no point have I invoked religious premises or theological arguments; yet Fetzer appears intent on diverting the discussion toward religion—particularly the Old Testament—which bears no direct relevance to the issues under consideration here. I will not allow this distraction to derail the discussion, but those interested in my detailed response can consult my previous engagements with Laurent Guyénot’s From Yahweh to Zion [here, here, here, here, and here].

“I am not arguing that Roe is right because it was adopted by the Supreme Court, but that it represents the right policy for the Court to have adopted. Jonas would have me citing the Supreme Court as an appeal to authority, when the validity of its conclusion is the question at stake.” I have challenged this very notion of viability, as it has been shown to be both scientifically and technologically untenable.

Moreover, it is historically inaccurate to claim that the Supreme Court reached its decision on Roe v. Wade “on independent grounds.” The abortion movement had long been influenced by elite interests—beginning with Margaret Sanger’s eugenic campaign and later advanced by figures such as the Rockefellers and other powerful groups seeking population reduction in the United States and abroad, including in nations such as Japan, South Korea, and Iran.

“I think his commitment to the pro-life as opposed to the pro-choice position has affected his objectivity in responding to my position.” This, however, is a classic case of begging the question. Fetzer’s own commitment to the pro-choice position has clearly clouded his objectivity in responding to my arguments—a point I will elaborate upon in this response.

As I have stated before, one of the most effective ways to test the validity of a moral or philosophical position is to examine its practical implications in the real world. I have provided three well-documented examples demonstrating that the consistent application of abortion policies has led to drastic population decline, in some cases approaching extinction-level demographics. It is therefore inaccurate to suggest that I have failed to approach this issue objectively. Why, then, does Fetzer refuse to engage with the historical evidence I have presented? Why do nations such as South Korea—where I have lived for the past sixteen years—now strongly oppose abortion? The answer is evident: they have witnessed firsthand the social and demographic consequences of such policies, which have brought the nation to the brink of demographic collapse.

Fetzer proceeds to argue that “Roe was right because it drew (what I take to be) the correct distinction between the first and second trimesters in the development of the fetus and the third, which (as he correctly observes) revolves around the concept of viability—the ability of the fetus to survive independently of the intrauterine environment—a capacity determined by lung rather than heart or brain development.” But why should the majority of people in the world accept this proposition as authoritative or morally sound? Moreover, what has become of the comprehensive critique I offered against this very theory in my second presentation? Once again, Fetzer appears not to have engaged seriously with the substance of my rebuttal before reiterating his position. He states:

“Absent the ability to survive independently of its mother, a fetus does not possess the crucial property of personhood with the legal, social, and moral properties thereby attained, bur remains a special kind of property of the gestating woman without its own independent standing.”

I have a six-month-old baby, and I can attest that he cannot survive independently of his parents; he requires the same kind of constant and specialized care that any unborn child would need. Likewise, my two-year-old daughter is not capable of independent survival apart from her mother and father. This is not a matter of abstract philosophy—it is an observable biological and developmental reality. Fetzer need only examine the evidence I have already presented, including that provided by scholars who themselves support abortion. For instance, Jeff McMahan, a well-known advocate of abortion rights, concedes that the viability and personhood argument is obsolete, since there is no coherent medical or scientific criterion that marks the precise moment when an unborn child suddenly becomes a “person.” McMahan’s own analysis thus undermines the very foundation of Fetzer’s appeal to viability.

I also presented substantial medical and technological evidence challenging the viability argument, yet Fetzer dismissed all of this as merely “the trivial truth.” Trivial truth? What exactly does that mean? Fetzer offered no clarification, presumably because this vague assertion serves as a convenient means of evading the evidence. When confronted with empirical and scientific challenges to their position, abortion proponents like Fetzer appear content to dismiss such data as “trivial,” as though scientific and technological realities could simply be brushed aside in favor of ideological conviction. In doing so, Fetzer and the intellectual elite effectively grant themselves the authority to ignore empirical truth whenever it conflicts with their predetermined ideological or political commitments—in this case, the unwavering belief that abortion is right regardless of what medical and technological evidence may reveal.

What, then, is the actual truth? Fetzer insists that “the law of biology—that the fetus cannot survive on its own without attaining lung development, which occurs at the end of the second trimester—remains intact. Viability remains viable apart from modern technology.” Yet this reasoning collapses under scrutiny. The so-called “law of biology” likewise dictates that a six-month-old infant cannot survive without the constant care and protection of a guardian. Does this biological dependence, then, grant parents the moral or legal right to terminate the child’s life if they so choose? The logic is plainly inconsistent. Dependency does not determine moral worth or personhood, and to ground moral judgment in biological self-sufficiency is to embrace a principle that would justify the destruction of any life deemed insufficiently autonomous.

Fetzer concedes that Kant would have opposed abortion but adds that “a more nuanced reading invites the response that the woman possesses rational agency herself, whereas the fetus is not (yet) a rational agent.” This reasoning, however, is circular. It presupposes the very point in dispute—namely, that the fetus lacks rational agency—without offering any coherent or empirically grounded criterion for determining when rational agency begins. Moreover, advances in medical science and embryology increasingly confirm that life begins at conception, thereby undermining the claim that the fetus is merely a potential rather than an actual human subject. To dismiss such evidence while appealing to a vaguely defined standard of “rational agency” is to substitute ideological speculation for biological reality.

Fetzer replies to my argument by asserting, “But surely, it’s not ‘sloganeering’ to observe that forcing women to carry unwanted fetuses to term is a form of reproductive slavery.” Let us grant this premise for the sake of argument. Consider a thought experiment: what about coercing the majority of the global population into accepting Fetzer’s view, grounded on the tenuous and scientifically questionable notion of “viability”? Would such coercion bear any resemblance to democracy? And what if one possessed the institutional power to enforce such a view—as organizations like Planned Parenthood and influential elites such as the Rockefellers effectively did in countries including Japan, South Korea, Iran, and elsewhere? If the result of such policies is a drastic reduction of population to the point of demographic extinction, then what more fitting term could there be than slavery? Moreover, if Fetzer’s definitions of viability and personhood do not constitute a clear case of begging the question, it is difficult to imagine what would.

Even more striking is Fetzer’s categorical assertion that “Pro-choice is democratic. Pro-life is not.” It is difficult to comprehend how such a statement can be sustained under any serious philosophical or historical scrutiny. Perhaps by “democratic,” Fetzer means that the elite and the powerful possess the right to impose their ideological will upon the rest of the world—and that any resistance to such imposition constitutes a rejection of democracy itself. If so, his definition of democracy bears little resemblance to its classical meaning. Whether Fetzer acknowledges it or not, his reasoning places him in ideological alignment with figures such as Margaret Sanger, the Rockefellers, and the proponents of Social Darwinism, whose doctrines were ascendant in Europe and America during the 1920s and 1930s and whose influence produced catastrophic moral and social consequences. Ironically, while Fetzer professes opposition to eugenics, his line of argumentation mirrors the very logic that once undergirded that movement.

Fetzer claims that I committed a “blunder” by asserting that Kant would have rejected abortion. Yet this is hardly a personal error, as I explicitly cited Kant scholars who affirm precisely this interpretation. More importantly, Kant’s own moral framework makes such a conclusion unavoidable. Abortion directly violates the categorical imperative, which requires that one act only according to maxims that can be willed as universal law. Can the maxim of abortion—that one may terminate nascent human life—be universalized without contradiction? If such a principle were universally adopted, the continuation of the human race would be impossible. The moral calculus is therefore not complex: universalizing abortion yields a population outcome of zero. By Kant’s own ethical standard, abortion cannot be justified.

Much of Fetzer’s rebuttal rests upon his particular conception of personhood—specifically, his claim that personhood does not extend to life within the womb. Yet this is precisely the point under dispute. Why should Fetzer’s definition be accepted as authoritative? By what philosophical or empirical criteria is it justified? And if we are operating within a Kantian framework, can such a criterion be universalized without contradiction? These are the central questions at stake. Fetzer’s commitment to his own definition of personhood compels him to presuppose the very conclusion he seeks to prove. Historically, this notion of personhood—as distinct from human life—emerged only after abortion advocates began constructing conceptual justifications for terminating life in the womb. In that sense, the definition itself is not a discovery but a post hoc rationalization.

With the advancement of medical science, the justification that once sought to obscure the biological reality of life in the womb has become increasingly untenable. Yet Fetzer continues to cling to it, dismissing modern embryological evidence as mere “trivial truth.” In effect, he urges us to disregard what medical technology has made indisputably clear. Even scholars and physicians with no ideological investment in the abortion debate affirm that human life begins at conception. Bradley M. Patten, in Human Embryology, writes: “It is the penetration of the ovum by a spermatozoan and the resultant mingling of the nuclear material each brings to the union that constitutes the culmination of the process of fertilization and marks the initiation of the life of a new individual.”[7] Likewise, Keith L. Moore observes in The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology: ““The cell results from fertilization of an oocyte by a sperm and is the beginning of a human being…Each of us started life as a cell called a zygote.”[8]

J. P. Greenhill and E. A. Friedman said: “The zygote thus formed represents the beginning of a new life.”[9]

Numerous other medical experts, obstetricians, gynecologists, and scientists have reached the same conclusion. For example, Bernard Nathanson—once a leading advocate for abortion—eventually became one of its most vocal critics after recognizing both the scientific and moral implications of fetal life. He later observed that many of the early proponents of abortion came from Jewish circles that sought to redefine life.[10]

Fetzer repeatedly asserts that “as long as the developing fetus has not attained the status of personhood, abortion (during the first two trimesters) cannot properly qualify as murder.” Yet he seems to overlook the central issue: why should anyone accept his definition of personhood in the first place? Even prominent proponents of abortion acknowledge that this definition is philosophically and scientifically fragile, and modern medical advances have rendered it increasingly obsolete. Fetzer then proceeds to assert—without argument—that “we have progressed at least this far by clarifying the status of personhood as the fundamental question about the moral status of abortion. Period!” This, however, is not clarification; it is mere dogmatism disguised as conclusion.

Fetzer objects when I state that the abortion issue has severe practical implications, particularly when I cite countries such as South Korea, Japan, and Iran. I was genuinely surprised by his response, as I assumed Fetzer agreed with Richard Weaver’s famous maxim that ideas have consequences. The abortion issue is not merely a philosophical or intellectual abstraction divorced from real-world outcomes. If that were the case, I would not have engaged in this discussion with him in the first place. More intriguingly, Fetzer appears to assume that my pro-life position stems solely from my Christian convictions. Yet must one be a Christian—or a Muslim, for that matter—to recognize that abortion can be fundamentally detrimental to any society that practices it persistently? Many governments currently attempting to recover from the consequences of widespread abortion are, in fact, secular rather than religious. Nevertheless, they have demonstrated the pragmatic awareness to acknowledge that the policy has failed and that it has been among the principal factors contributing to their nations’ demographic decline.

Returning to Kant, we see that abortion policies have been implemented in the countries I mentioned, and the consequences have been significant enough to compel their governments to reconsider their positions. In South Korea, for instance, the government now offers financial incentives for women not only to keep their babies but to have more children, as the nation faces a demographic crisis. These are indisputable facts. Should we not all be concerned about such developments? Should these governments abandon their efforts to increase birthrates? Yet Fetzer proceeds to declare that

“The consequences that may follow from the truth of an assertion is not a reason for denying its truth–at least, not in a philosophical forum. It qualifies as a fallacious appeal to pity. While I have no reason to dispute the facts he asserts to be the case for those nations whose demographic problematics he describes, none of that is relevant to the question of the morality of abortion.”

I am genuinely astonished by Fetzer’s claim, particularly because he is well aware of Kant’s categorical imperative, which holds that for any moral or philosophical system to be valid, it must be capable of universalization and its applications must remain logically and ethically consistent. If a system cannot withstand this test, how can it possibly be considered true? Thus, to even imply that the social and political consequences of abortion fall outside the scope of the debate is, in my view, an attempt to evade the central moral challenge. Moreover, to dismiss those who oppose abortion as merely “Neanderthal in their thoughts and attitudes” is not a serious engagement with the moral or empirical dimensions of the issue—it is a rhetorical evasion that fails to address the reality before us.

Abortion as Industry: The Business Behind Reproductive Rights

Since Fetzer raises the “Neanderthal” issue, it is worth reminding him—and interested readers—that abortion has also generated enormous financial profit. For a detailed examination of this issue, I refer readers to Katherine J. Parkin’s recent study, The Abortion Market: Buying and Selling Access in the Era Before Roe (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2025), as well as Sarah Elvins and Katherine Parkin’s article, “The Business of Abortion: Referral Services, Cross-Border Consumption, and Canadian Women’s Access to Abortion in New York State, 1970–1972,” published by Cambridge University Press. Elvins and Parkin note that “relatively less attention has been spent exploring how abortion became a site of entrepreneurial growth in the 1960s and 1970s because not only activists hoping to advance women’s health, but also business and medical professionals, saw the potential for profit and became involved in the business of abortion.”[11]

Even Lore Perron, president of the Association for the Repeal of Canadian Abortion Laws, who acknowledged that abortion agencies provided some assistance to women, expressed concern that “these agencies prioritized profits at the expense of desperate women.”[12]

In addition, “profit-motivated doctors”[13]

recognized the potential to capitalize on the emerging abortion movement.

Other individuals and groups soon recognized the same opportunity for profit. For example, “Oak Park, Michigan, manufacturer Martin Mitchell, who had no background in medicine, saw an opportunity to profit by providing chartered air flights to clinics and hospitals in New York for women seeking abortions. Former insurance salesman Ken Oliver had a chartered limousine service that took clients from Detroit to New York clinics—he noted, ‘of course I’m in this business for the money. And business is almost too good.’”[14]

Parkin demonstrates that, even before Roe v. Wade, the abortion industry generated at least 750 million dollars annually for elites and affiliated organizations. Drawing extensively on archival documents, Parkin reveals that the abortion industry constituted “a burgeoning trade, made up of profit-driven hospitals and male doctors, entrepreneurial brokers, and compassionate providers.” These actors were, as she argues, not merely medical professionals but “ideologues” committed to population control and eugenics—an ideological and financial nexus that “played a central role in advancing the legalization of abortion.”[15]

Parkin discovered that organizations such as the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL), Planned Parenthood, and the Guttmacher Institute “sprang from eugenicists and population control ideologues.”[16]

This means that by defending the ideology these figures helped perpetuate, Fetzer aligns himself—perhaps unintentionally—with their legacy. Parkin further observes that had it not been for these ideologues, “the United States would not have secured the right to legal abortion.”[17]

Here, Parkin effectively exposes the historical reality: if abortion became legalized primarily through the influence of a small group of elite activists, how can Fetzer plausibly maintain that abortion represents democracy? And if Fetzer still doubts this, Parkin continues her analysis with striking precision: “Like the third co-founder of NARAL, Dr. Lonny Myers, early abortion activists were not motivated by women’s personal liberty, but instead mobilized for population control.”[18]

According to her findings, “men and women of wealth, power, and pseudoscientific fixations shaped the evolving abortion market in the twentieth century.”[19]

To describe such a movement as “democratic” is, therefore, a profound distortion of historical fact. It was, as Parkin demonstrates, a system rooted in population control, eugenics, and financial profit. Consider, for example, William Jennings Bryan Henrie, who admitted in 1938 to performing twenty thousand abortions and earning eight million dollars in profit. Between 1957 and 1962—his final five years in practice—he reportedly conducted a thousand abortions annually.[20]

Is this kind of ideological maneuvering still taking place today? Undeniably so. Consider, for instance, Francis Collins—arguably one of the most influential scientists of the 2000s—who identifies as an evangelical Christian yet remains firmly committed to the Darwinian framework.

Collins oversaw research that used “body parts collected from aborted human fetuses to create humanized mouse and rodent models with full-thickness human skin.” In this experiment, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh dissected human fetal spleen, thymus, and liver tissues into small pieces and transplanted them, along with hematopoietic stem cells, into irradiated mice. Human skin tissue was also grafted onto the mice.

The fetal organs used in these experiments were obtained from aborted fetuses between 18 and 20 weeks of gestation—a stage at which the unborn child exhibits brain waves and a beating heart, can hear sounds, move limbs and eyes, and has a functioning digestive system.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) appeared aware that the nature of this research could provoke outrage among the majority of people in the United States, as they sought to withhold details from the public. Judicial Watch and the Center for Medical Progress were compelled to file a lawsuit to obtain documentation of the experiments. Collins ultimately and reluctantly released the information. Judicial Watch noted that approximately three million dollars of taxpayer funds were allocated to the research.[21]

A significant amount of money is involved in this matter, and this economic dimension cannot be easily dismissed. Even an examination of Planned Parenthood reveals that, in 2013–2014, approximately 22.6% of its clinic revenue was derived from abortion-related procedures.[22] Between 2022 and 2024, reports indicate that Planned Parenthood performed approximately 390,000 to 400,000 abortions annually while receiving hundreds of millions of dollars in government grants.[23]

How much money are we talking about here? 700 million dollars![24] In effect, taxpayer funds continue to subsidize these procedures. Other estimates place the total at approximately 800 million dollars, translating to nearly 2 million dollars per day.[25] One may reasonably ask what the average American could do with two million dollars. Could such funds not be more effectively directed toward assisting citizens who continue to be disadvantaged or overburdened by the health insurance system?[26]

In 2024, leaked emails from Planned Parenthood reportedly revealed that the organization sought fetal specimens up to six months in gestational age for purported “research” purposes. The institution involved in this activity was the University of California, San Diego. One of the emails stated: “We will collect tissues from fetuses ranging from 4 to 23 weeks gestational age from subjects undergoing elective surgical pregnancy termination at Planned Parenthood in San Diego.”[27] Can Fetzer, then, reasonably claim that this, too, constitutes an expression of democracy?

Fetzer vs. Kant

When I stated that only a small minority continues to advocate for the normalization of abortion, I was referring to the global population as a whole, not to disagreements among members of the elite. Taken collectively, the data indicate that the overwhelming majority of people support the protection of life rather than the expansion of abortion rights.

Fetzer accuses Kant of doing a “whack job” because he regarded onanism and homosexuality as forms of self-destruction. What Fetzer fails to acknowledge, however, is that Kant’s position is entirely consistent with his categorical imperative. To repeat, Kant sought to evaluate moral actions according to whether they could be universalized without contradiction, and in this sense, his view on these practices coheres with his broader ethical framework. Moreover, contemporary psychological and sociological research has documented the potentially detrimental effects such behaviors can have on individuals, further underscoring Kant’s philosophical consistency rather than undermining it.[28]

For those seeking a concrete historical example, one might turn to Michel Foucault, whose life and death have often been cited in discussions about the personal consequences of certain sexual practices—he ultimately died of AIDS, a disease closely linked to such behaviors. Furthermore, substantial medical and psychological research has documented the potential harms associated with homosexual practices, both physiologically and emotionally. From a broader historical perspective, the Cambridge and Oxford anthropologist J. D. Unwin demonstrated in his 1934 study Sex and Culture that societies enforcing strong restraints on sexual behavior tend to achieve higher levels of cultural and moral development, whereas those that embrace sexual permissiveness often undergo intellectual, moral, and civilizational decline.[29] Aldous Huxley—the same thinker who candidly admitted in Ends and Means that “we object to morality because it interferes with our sexual freedom”—also recognized the significance of Unwin’s scholarship, describing Sex and Culture as “a work of the highest importance.”[30]

Fetzer claims, “Here we have Jonas himself citing Kant as his appeal to authority for opposing masturbation and abortion.” Yet he overlooks a crucial point: Fetzer himself frequently supports his arguments by appealing to authorities who have historically been mistaken. My reference to Kant is not an appeal to infallibility, as if his reasoning were beyond critique like a Supreme Court decision. Rather, I invoke Kant because his arguments are philosophically coherent and their application aligns with observable realities in the world. It is that straightforward.

If Fetzer continues to object, he only reinforces my position, because the Darwinian version he defends in Render unto Darwin rests on a similar type of appeal to authority. I would challenge him to examine MacDonald’s Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition, in which MacDonald invokes Darwinian principles to substantiate his arguments. As Richard Dawkins himself acknowledged: “Although atheism might have been logically tenable before Darwin, Darwin made it possible to be an intellectually fulfilled atheist.”[31]

Fetzer himself appeals to authority. If he wishes to examine his own position, he relies heavily on Carl G. Hempel as an authoritative figure. Indeed, Fetzer explicitly acknowledges that both his undergraduate work and his ongoing engagement with the philosophy of science are grounded in Hempel’s principles. Therefore, if Fetzer criticizes me for citing Kant, should he not also question whether Princeton should have rejected his undergraduate thesis for relying on Hempel as an authority? Of course, he might respond that he appeals to Hempel because Hempel’s philosophy is correct. But that same defense applies equally to my use of Kant.

Fetzer writes, “As for universalizability, we are not talking about every woman aborting every fetus but every woman having the right to determine whether or not to bear her fetus to term, which is another thing.” Yet Kant scholars have addressed precisely these nuances, and it is surprising that Fetzer seems unwilling to engage with their analyses. The critical point he overlooks is this: Kant’s categorical imperative still applies. What is the moral significance of granting a woman the right to decide whether to abort a fetus if the action itself cannot be universalized in a coherent and philosophically applicable way? Without such applicability, the notion of a “right to decide” loses its ethical and logical grounding. Fetzer appears to frame his argument purely in theoretical terms, effectively removing any consideration of the real-world practicability of his claims.

The real world, however, does not operate in this abstract manner. As I have already demonstrated, the consequences of abortion policies can be observed in countries such as Japan, South Korea, and Iran. Fetzer’s real challenge, then, is to identify a society that has implemented abortion extensively while still flourishing culturally, morally, and demographically. If he can provide such an example, his case would be considerably strengthened.

South Korea Destroys the Pro-Choice Position

Fetzer claims that I did not address CA-4, yet I contend that this issue has already been covered through the practical examples I provided—namely, South Korea, Japan, and Iran—which illustrate the real-world consequences of abortion policies. For instance, any serious governmental agency in South Korea would confirm that the practice of abortion has already been implemented and has demonstrably failed. South Korean scholars Sunhye Kim, Na Young, and Yurim Lee document that from the 1960s through the 1980s,

“abortion, contraception, and sterilization were widely encouraged to reduce the nation’s total fertility rate and, in some cases, were even used coercively among certain populations, including women with disabilities. During this period, the South Korean government established family planning clinics nationwide that provided abortion services under the name of menstrual regulation, and the government offered strong incentives such as public housing and health insurance benefits to families who had less than two children.”[32]

Kim, Young, and Lee further observe that “people with disabilities, single mothers, and poor mothers were often subjected to forced abortions.” In the process, “many Korean women had abortions during their lives,”[33]

a practice that has contributed to the nation’s current demographic crisis, with the population now on the brink of extinction. By the mid-2000s, the government recognized that the nation was on a path toward demographic collapse and consequently concluded that abortion policies had to be reversed.[34]

By 2019, Join Act—a small activist coalition that in no way represented the broader consensus of the Korean population—”played a central” role in pressuring the Supreme Court to overturn the nation’s abortion ban,[35]

effectively nullifying the will of the majority. “In the history of the Korean women’s rights movement, their efforts to legalize abortion represented the first mass movement in South Korea that foregrounded women’s reproductive rights and health issues, including abortion rights.”[36]

Once again, as has occurred in numerous countries around the world, the opinion of a vocal minority supplanted the overwhelming consensus of the majority. For Fetzer to even remotely suggest that such a process constitutes democracy is, quite frankly, untenable.

The Korean government is fully aware that the legalization of abortion poses a demographic threat—a veritable time bomb that could hasten population decline—yet it continues to face mounting international pressure, particularly from organizations such as the World Health Organization, to authorize and expand access to abortion pills. As a result, the government decided that it had to navigate carefully, lest it risk being perceived as out of step with the so-called free world. “The major goal of South Korea’s population policies was to reduce the total fertility rate so that the country could receive international aid for economic development.”[37]

South Korea’s fertility rate, which stood at 6.0 in the 1960s, fell sharply to 4.5 in the 1970s, 2.8 in the 1980s, and 1.6 by the 1990s. By 2023, South Korea’s fertility rate had plummeted to an astonishing 0.72, the lowest in the world and a clear indication of the country’s deepening demographic crisis.[38] The picture becomes even more troubling when examining abortion statistics: “In South Korea from 1989 to 2009, the number of abortions was estimated to range from 30 million to 50 million annually.”[39]

By 2005, the South Korean government began to awaken to the gravity of the demographic crisis it had helped to create: “In 2005, to boost this rate, the South Korean government passed the Framework Act on Low Birth Rate in an Aging Society, revived the enforcement of the criminal codes on abortion, and set up The master plan for the prevention of illegal abortion. Furthermore, Minister of Health and Welfare Jae Hee Chun acknowledged that the government was establishing abortion prevention policies to stimulate population growth, explaining that halving the abortion rate would significantly increase the country’s total birth rate.”[40]

In 2012, the court’s ruling was unambiguous: “the fetus’s right to life is in the public interest,” whereas “a woman’s right to choose abortion is in an individual’s interest.” Consequently, the court concluded that “women’s rights cannot take precedence over the fetus’s right to life.”[41]

However, pro-abortion advocates and feminist movements continued their campaign. Between 2016 and 2019, the organization Joint Action “lobbied political parties, government ministries, and activist groups to submit amicus briefs to the Constitutional Court.” As a result of these coordinated efforts, several influential bodies—including the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, the National Human Rights Commission of Korea, and the Green Party Korea—submitted amicus briefs urging the government to amend the existing criminal codes on abortion to safeguard what they described as women’s rights, including the right to terminate a pregnancy.[42]

In 2019, the court—succumbing to the demands of elite actors and NGOs, including the feminist movement in Korea—struck down the country’s ban on abortion. Nevertheless, the government, fully cognizant of the demographic and social implications, has still not legalized abortion pills, although some women are able to obtain them illegally online.[43] Thus, we are confronted with the profound social consequences of abortion. An observer may choose to dismiss these realities as mere “trivial truths,” or he may confront them honestly, allowing his ideology to yield to the demands of truth.

Fetzer Against Ruse and Wilson on Morality

After I highlighted a fundamental contradiction in the work of Michael Ruse and E. O. Wilson, Fetzer conceded the point, stating: “While I like Wilson and Ruse and have conversed with them on occasion, my conclusion has long been that they had no grasp of the nature of morality or of why morality distinguishes the human species above all others.”

Welcome to the club, Fetzer! This critique has long been my central issue with anyone—including Kevin MacDonald—who encourages readers to embrace Darwinism without clearly explaining the metaphysical assumptions that underlie it. In this regard, Fetzer and I are in agreement, and he would have strengthened Render unto Darwin considerably by explicitly addressing these issues. In my forthcoming interaction with Kevin MacDonald, I intend to lay out these contradictions in detail.

There were several questions I raised in my previous presentation that appear to have gone unanswered. For instance, I specifically inquired about a quotation from Fetzer’s book The Evolution of Intelligence, which he may have overlooked. Nevertheless, I recognize that Fetzer has made a sincere effort to respond to the questions posed, and the dialogue throughout this discussion has been consistently cordial, despite our continuing and substantive disagreements on these issues. Any outstanding points that remain unresolved can, of course, be addressed further in the comment section.

I would also like to thank Fetzer for contacting Kevin MacDonald and inviting him to participate in these discussions. MacDonald has agreed to join, and our next dialogue will focus on Darwinism, MacDonald’s own views, and his responses to key challenges. I believe this will be a highly productive endeavor for readers of all perspectives. My only request to readers is to engage with these discussions critically and thoughtfully: keep your thinking cap firmly on. While emotion can be a virtue when applied appropriately, it must take a back seat when evaluating truth, empirical evidence, and metaphysical reality. Readers should pay close attention to logical fallacies, incoherent arguments, flawed premises, and historical precedents throughout the dialogue.

James Fetzer’s Third Response to Alexis Jonas

James Fetzer, Ph.D.

Jonas Alexis displays many intellectual virtues: he’s highly intelligent, thorough and systematic, deeply researched and knowledgeable about the issues. Yet (as I shall contend here) he commits (at least) three argumentative blunders (which appear to even qualify as “category mistakes” by treating things of one kind as though they were things of another) with regard to (1) the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade, (2) the scope of evolutionary explanations, and (3) the characteristics of deontological moral theory. Jonas does not stand alone in these respects, where E.O. Wilson, Michael Ruse, Daniel Dennett and other worthies commit similar if not the same intellectual mistakes.

MISCONCEPTIONS

(1) Roe v. Wade

While I believe Roe was properly decided and that sending it back to the states was wrong, Jonas mistakenly implies that I cite Roe to justify Roe and thereby beg the question. Thus he contends,

“I never asserted that Fetzer was using Roe as a premise in his reasoning. I made it clear that “Fetzer repeatedly invokes Roe v. Wade in support of his thesis—both in the article under discussion and in his book Render unto Darwin.” I was careful to note that he supports his argument by appealing to Roe, not by presupposing it as a premise. Thus, his characterization is inaccurate.”

But if I were “appealing to Roe“, as Jonas claims, I would be (in effect) treating it as a premise and thereby beg the question. He accurately observes that SCOTUS rulings are mixed and that, from time to time, they are egregiously wrong, which no one would dispute.

Indeed, in the context of his subsequent discussion of several cases where SCOTUS appears to have made wrong decisions, he reaffirms his implicit contention that I take Roe for granted:

“The only decision he embraces—or invokes to justify his position—is the Court’s endorsement of abortion. But why the selective reasoning? Why not appeal to Buck v. Bell? Why not to Korematsu v. United States? Or to Bowers v. Hardwick, in which the Court criminalized consensual homosexual conduct? Fetzer, naturally, would reject any of these as moral precedents. Yet, when the Supreme Court upholds abortion, he insists that such a ruling must be accepted as morally sound.”

What I find most interesting here is that Jonas does not appear to be aware that he is thereby contradicting himself about my position vis-a-vis Roe and the Supreme Court itself.

Where he goes wrong is that I differentiate between explaining the meaning of Roe and explaining why Roe was rightly decided. By dividing gestation into three trimesters and declaring abortion to be permissible unrestrictedly (during the first), subject to regulation in performance (during the second), but only permissible to save the life or the health of the mother (during the third), the court thereby implied that the first primitive legal “right to life” occurs at the end of the second trimester, which happens to coincide with (long standing) criteria of viability, where the fetus attains the ability to survive apart from its intrauterine environment.

That’s my take on the meaning of Roe. Viability turns out to be a function, not of heart or of brain activity, but of the development of the lungs sufficient to enable the fetus to survive apart from its mother’s womb. That advances in medical technology may enable fetuses at earlier stages to exist in artificial wombs does not undermine the point that, historically and medically, viability has been acknowledge as a turning point in the development of the fetus, where prior to viability the fetus properly qualifies as a special kind of property of the gestating mother. Viability thus marks the development of the fetus to the status of personhood.

Turn the question around. No one but a lunatic would deny that a baby born live has the legal, social, and moral standing conferred by personhood. And (I would infer) virtually no one but a lunatic would insist that a zygote or an embryo has the legal, social, and moral standing conferred by personhood. The issue thus becomes, Where do we draw the line? Look at some of these stages of embryogenesis and ask yourself, Does it make any sense at all to regard these entities as persons?

I have long believed that much of the debate over abortion arises because of misconceptions of the developing entity as looking like a little person, which might inspire such bizarre beliefs. But when you look at the sequence of developmental stages from zygote to live birth, the point at which biology and morality appear to converge is at the state of viability.

The right-to-life movement, as I perceive it, has focused overly much on whether the entity developing from a zygote to an embryo to a fetus (and eventually emerging as a live birth) represent stages in the development of the life of a human being, to which the answer is obvious and trivial. OF COURSE the developing entity represents stages in the development of the life of human beings. That is not the question but rather, At what point in those stages of development does the fetus qualify for the legal, moral, and social status of being a person? My argument is that viability is that stage, which explains why Roe was properly decided.

(2) Evolutionary Explanations

Had Jonas read The Evolution of Intelligence (2005), he would realize that it expounds differences between genetic and cultural evolution, which are not remotely the same. Genetic evolution is constrained by laws of gestation, where it takes nine months (on the average) to produce another human being from its parents. While we measure the course of evolution by changes in gene pools across time, genetic evolution tends to take vast intervals of time to emerge as functions of the mechanisms of speciation (genetic mutation, sexual reproduction, genetic drift, and genetic engineering) and of selection (natural selection, sexual selection, group selection, and artificial selection).

The situation with regard to cultural evolution is completely different. Fads and fashions are capable of spreading like wildfire within a population, depending upon the modes of communication available to that population. Given the advent of radio and television, new songs and novel attire (including the latest brands of sports’ ware and tennis shoes) can surge within a community or subpopulation thereof (such as teenagers or pre-teens). These are properties that can come and go while those who adopt and later discard them remain one and the same. They are transient properties amenable to change over time, which differentiate them from those acquired by virtue of genetic change.

The behavioral capabilities of a species are rooted in their genes. Too often, it seems, students of evolution (especially of sociobiology) confound transient properties with permanent, which cannot be altered and cannot be changed without altering the genes of the organisms displaying them. Thus, there are ranges of behavior permitted by our genes that are affected by our environment and our culture. Studies of identical twins (who are genetically the same) raised apart (in different environments) have established that about 60% of our behaviors are innate and rooted in our genes, but the other 40% (including our attitudes and behavior toward our fellow man) are subject to variation.

That much should be obvious from reviewing the history of humanity and of man’s capacity for abusing his fellow man. Murder, robbery, kidnapping, and rape are examples of behavior humans have displayed toward other humans in the course of history. But so too are honesty, loyalty, courage, and integrity, which exemplify the best in human conduct and are not determined by our genes. E.O. Wilson was brilliant in separating human beings from the social insects (bess, ants, wasps, and the like), whose behavior is (or at least appears to be) 100% innate and instinctual. Humans rise above the social insects because our behavior (to roughly 40%) can be subject to personal or environmental control.

When I review alternative theories of morality–including four popular theories: subjectivism, family values, religious-based ethics, and cultural relativism; and four philosophical theories: ethical egoism, limited utilitarianism, classic utilitarianism, and deontological moral values–no one doubts that they all have examples within the human community in historical perspective, where consequentialist theories— ethical egoism, limited utilitarianism, and classic utilitarianism— judge the rightness or wrongness of actions in terms of the benefits they bestow upon the individual, the group, or the entire population regardless of their consequences for others (beyond the person, the group. or the population).

(3) Deontological Moral Theory

Thus, JunkyardDog, for example, has argued that Darwinian theory is deterministic and leaves no room for moral choice or “freedom of the will”, as he concisely contends:

“Any consistent Darwinist explanation rules out anything but a deterministic explanation for morals and ethics. Darwinist evolution (or neo-Darwinism, or the Modern Synthesis) doesn’t just “dispose us to act in certain ways,” but claims as its axiomatic starting point that those dispositions are the result of blind, purposeless forces. Everything within Darwinian naturalism that occurs becomes irrefutable evidence that human thoughts must arise independently of intent or purpose. As a Darwinist you need to prove or at least persuasively argue that human thought is not so determined before making what, in terms of evolutionary naturalism, is the unwarranted claim that not everything is so determined. In fact, it appears you’re asking us to accept a case for free will and teleological purpose within the Darwinian paradigm on grounds Darwinism rules out.”

As I replied at the time, your argument is that normative (moral) behavior would violate the laws of evolution and therefore represents mere wishful thinking from a Darwinian point of view. That would be true but for the development of human minds from their animal precursors which enable humans to contemplate possible situations that differ from present circumstances, some of which may represent more desirable circumstances than others. As I explain in The Evolution of Intelligence (2005) — which I would love for him to critique — there are kinds (or levels) of minds as semiotic (or sign-using) systems from iconic sign-using minds to indexical sign-using minds to symbolic sign-using minds and higher, including the capacity for reasoning and (at the highest level) the use of signs to criticize other uses of signs as meta-mentality. See

The contemplation of situations that differ from those that obtain (under appropriate conditions of motive, belief, ethics, abilities and capabilities) enables humans to consider how things could change for the better to improve the quality of their lives. Certainly, being treated as persons with respect for their rights has obvious benefits over being treated, for example, as subservient slaves. The exercise of reason thus enables us to transcend our evolutionary origins. Free will does not entail uncaused behavior but rather behavior that represents our preferences and not under coercion or constraint. The influence of drugs or defects can affect cognitive competence, but for most of us most of the time we are able to act in accordance with our motives, beliefs, ethics, abilities and capabilities–and are thereby acting freely. He and others might also like my Philosophy and Cognitive Science (2nd ed., 1998).

FROM DARWIN TO DEONTOLOGY

Even though Jonas agrees with my adoption of an objective (deontological) standard of morality, he thinks I haven’t done enough to escape the clutches of Darwin even with respect to morality:

“Fetzer and I concur that objective morality ‘elevates the human species above all others,’ and that certain groups—such as Israeli Zionists—have forsaken their moral potential by perpetrating acts of genocide against the Palestinians in order to seize their land. In this respect, we stand in agreement with Fetzer. Yet the crucial point remains that the Darwinian framework categorically denies the existence of objective morality, thereby placing Fetzer in a philosophically untenable position within the Darwinian fraternity. In this sense, he becomes something of an intellectual outlier, if not an outright dissident, among his Darwinian peers.”

On Jonas’ account, “the Darwinian framework” denies the existence of objective morality; since I endorse the existence of objective morality, I must (to be consistent) reject “the Darwinian framework”. But while evolution can explain human behavior to the extent to which it has genetic determinants, the emergence of reason and rationality enables us to establish the existence of objective morality and rise above our biology with behavior that exemplifies objective morality.

JunkyardDog likewise seems to think thought is a “package deal” where, if you regard evolution as real — and nothing in biology makes sense absent evolution — you must accept a “Darwinian” account of ethics and morality. I am a philosopher of science and recognize a sophisticated version of evolution — which entails (at least) four mechanisms for speciation (genetic mutation, sexual reproduction, genetic drift, and genetic engineering) and four others for selection (natural selection, sexual selection, group selection, and artificial selection) — as indispensable to explain the phenomena (diversity of species, the fossil record, morphological similarities and the like. There simply are no viable alternative explanations.

He also commits a category mistake in presuming that evolution has the ability to explain morality and ethics (or their absence within a deterministic framework). What he fails to appreciate, therefore, is that Homo sapiens as the highest form of evolution in the animal kingdom possesses concomitant intellectual abilities that far transcend those of lower species, where there are “more things in Heaven and Earth than are dreamt of in his philosophy”. What I like about his having staked out his position so clearly and concisely is that he thereby emphasizes a key misconception about the relationship between evolution, human thought, and our capacity to act in ways that manifest morality.

The higher species (of course) have properties lower species lack. Among them are mental properties that are distinctive of Homo sapiens, which I investigated in The Evolution of Intelligence (2005). Darwin was a smart guy but that doesn’t mean he has the final word even on matters falling within the domain of evolution. For example, my articulation of these eight evolutionary causal mechanisms is superior to Darwin’s — and there may be other mechanisms I have overlooked. My research on the nature of mentality and its evolution from lower to higher species builds on the theory of signs advanced by the (only) great American philosopher, Charles S. Peirce, for whom minds are also sign-using systems.

They both seem to have an “off the shelf” version of evolution that begins and ends with Darwin. I am no more devoted to Darwin’s thoughts about evolution and ethics than I am about Kant’s reflections on abortion and masturbation — yet I regard Kant as one of “The Big Three’ in the history of philosophy — along with Aristotle and Peirce. Just as my philosophical work on scientific explanation combines a Popperian conception of laws with an Hempelian analysis of arguments (qualified by appropriate conditions of relevance and specificity), my work on the evolution of mind, consciousness, and cognition combines a Peircian conception of mentality within an evolutionary framework initially inspired by Darwin.

Evolutionary theory is vastly richer and rewarding than simplified models of genetic mutation and natural selection. The emergence of the human mind enables us to contemplate modes of relations between conspecifics that transcend our animal origins. We may have (pre) dispositions toward the exercise of might to benefit ourselves, our families, our societies and (even) our species with regard to survival and reproduction. But once we appreciate that we are obligated as moral creatures to treat others of our species with respect — and rule out methods that lower species follow — we attain the dignity of human beings and thereby transcend our evolutionary origins, as I have sought to explain in these essays.

OBJECTIONS AND REFUTATIONS

It’s difficult for me to appreciate Jonas’ arguments absent a commitment on his part to the existence of immoral souls or to the inherent sanctity of human life from the moment of conception. That may explain why, even though my arguments are both scientifically and philosophically sound, he wants to dispute them on a variety of grounds of unequal worth. Thus, for example, he asserts that six-month old infants cannot survive with care and nurturing, which is obviously correct:

“What, then, is the actual truth? Fetzer insists that ‘the law of biology—that the fetus cannot survive on its own without attaining lung development, which occurs at the end of the second trimester—remains intact. Viability remains viable apart from modern technology.’ Yet this reasoning collapses under scrutiny. The so-called ‘law of biology’ likewise dictates that a six-month-old infant cannot survive without the constant care and protection of a guardian. Does this biological dependence, then, grant parents the moral or legal right to terminate the child’s life if they so choose? The logic is plainly inconsistent. Dependency does not determine moral worth or personhood, and to ground moral judgment in biological self-sufficiency is to embrace a principle that would justify the destruction of any life deemed insufficiently autonomous.”

The point about viability I intend is far simpler and direct: the fetus cannot live on its own (for any period of time) prior to the attainment of viability. It cannot even breathe. So the fact that medical and technical developments can keep it alive under conditions that replicate or simulate those of the intrauterine environment really don’t matter. When can a fetus live on its own — even for only a relatively brief duration? Biology answers the question, but Jonas doesn’t like the answer.

There may be a massive blunder here embodied in the first sentence, because Jonas appears to believe that I maintain that “personhood does not extend to life within the womb”. Maybe this misperception — which frankly baffles me — has affected his interpretation of my stance, which is that personhood occurs at the end of the second trimester.

“Much of Fetzer’s rebuttal rests upon his particular conception of personhood—specifically, his claim that personhood does not extend to life within the womb. Yet this is precisely the point under dispute. Why should Fetzer’s definition be accepted as authoritative? By what philosophical or empirical criteria is it justified? And if we are operating within a Kantian framework, can such a criterion be universalized without contradiction? These are the central questions at stake. Fetzer’s commitment to his own definition of personhood compels him to presuppose the very conclusion he seeks to prove. Historically, this notion of personhood—as distinct from human life—emerged only after abortion advocates began constructing conceptual justifications for terminating life in the womb. In that sense, the definition itself is not a discovery but a post hoc rationalization.”

During the third trimester, the developing fetus has the status of being a person with the first and most primitive “right to life” absent abortion to save the life or the health of the mother, whose primacy in conflict stands as superior to that of the fetus. But how could Jonas — after our extensive and detailed exchanges — get this basic aspect of my position completely wrong?

Notice, too, he once again implies that I have begged the question by explaining and defending (what I take to be) the appropriate conception of personhood, when I have done nothing of the kind. His devotion to Kant and the principle that moral actions must be ones that could be universalized (or made laws of nature) yields another line of criticism:

“Fetzer accuses Kant of doing a ‘whack job’ because he regarded onanism and homosexuality as forms of self-destruction. What Fetzer fails to acknowledge, however, is that Kant’s position is entirely consistent with his categorical imperative. To repeat, Kant sought to evaluate moral actions according to whether they could be universalized without contradiction, and in this sense, his view on these practices coheres with his broader ethical framework. Moreover, contemporary psychological and sociological research has documented the potentially detrimental effects such behaviors can have on individuals, further underscoring Kant’s philosophical consistency rather than undermining it.”

The practices of masturbation and (even) of homosexuality are themselves both universalizable, where the former has (to the best of my knowledge) no serious damaging social effects but the latter presumably would lead to the extinction of the species, opposition to which would require a commitment to the value of the existence of Homo sapiens. Similar concerns apply to his reflections on the social and population policies of other nations, such as South Korea.

Among the oddest of his objections to my position strains credulity. Hempel was the most influential philosopher of science among philosophers of science of the past 100 years. He was certainly an inspiration for my own philosophical research, especially with regard to his concept of explication and the crucial role in argument of criteria of adequacy. But Jonas’ take misses the mark:

“Fetzer himself appeals to authority. If he wishes to examine his own position, he relies heavily on Carl G. Hempel as an authoritative figure. Indeed, Fetzer explicitly acknowledges that both his undergraduate work and his ongoing engagement with the philosophy of science are grounded in Hempel’s principles. Therefore, if Fetzer criticizes me for citing Kant, should he not also question whether Princeton should have rejected his undergraduate thesis for relying on Hempel as an authority? Of course, he might respond that he appeals to Hempel because Hempel’s philosophy is correct. But that same defense applies equally to my use of Kant.”

My undergraduate thesis was on the logical structure of explanations of human behavior, where The Evolution of Intelligence (2005) brings my philosophical work full-circle. I have not simply emulated Hempel but have become a major critic of Hempel (see, for example, “The Paradoxes of Hempelian Explanation” and have sought to improve upon the conditions he imposed for scientific explanations to qualify as adequate. Unlike Jonas in relation to Kant, my attitude has been to improve upon his efforts.

Perhaps the most bewildering of Jonas’ complaints, however, is his denial of the obvious: that pro-choice is democratic while pro-life is not. We may be in agreement that E.O. Wilson and Michael Ruse have not fully grasped the nature of morality, but I am taken aback that he does not appear to appreciate the coercive character of the pro-life position:

“Even more striking is Fetzer’s categorical assertion that ‘Pro-choice is democratic. Pro-life is not.’ It is difficult to comprehend how such a statement can be sustained under any serious philosophical or historical scrutiny. Perhaps by ‘democratic,’ Fetzer means that the elite and the powerful possess the right to impose their ideological will upon the rest of the world—and that any resistance to such imposition constitutes a rejection of democracy itself. If so, his definition of democracy bears little resemblance to its classical meaning.”

Forcing a woman to carry an unwanted fetus to term is a form of reproductive slavery. We know that slavery is wrong, if any forms of human conduct are wrong. It’s the ultimate manifestation of treating others merely as means. Perhaps the greatest benefit of the pro-choice position, therefore, is that it respects every woman’s right to make the determination of whether or not to carry a fetus to term her choice (in consultation with her advisors under her personal and particular circumstances). Which is why I regard the pro-choice position as the only defensible position that is democratic, American, and moral.

James Fetzer, Ph.D., is Distinguished McKnight Professor Emeritus on the Duluth Campus of the University of Minnesota.

Notes

[1] See Wendy Ng, Japanese American Internment During World War II: A History and Reference Guide (Westport: Greenwood Press, 2002).

[2] For historical studies, see John Koster, Operation Snow: How a Soviet Mole in FDR’s White House Triggered Pearl Harbor (Washington: Regnery Publishing, 2012); Thomas Fleming, New Dealers’ War: FDR and the War Within World War II (New York: Basic Books, 2001); Robert B. Stinnett, Day Of Deceit: The Truth About FDR and Pearl Harbor (New York: Touchtone, 2000).

[3] Thomas Fleming, New Dealers’ War: FDR and the War Within World War II (New York: Basic Books, 2001), 257.

[4] Ibid., 255-256.

[5] Ibid., 257.

[6] Ibid., 258.

[7] Bradley M. Patten, Human Embryology , 3d ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 1968), 43.

[8] Keith L. Moore, The Developing Human: Clinically Orìented Embryology , 2d ed.

(Philadelphia, Penn: W.B. Saunders, 1977), 1 and 12.

[9] J. P. Greenhill and E. A. Friedman, Biological Principles and Modern Practice of Obstetrics (Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1974), 17.

[10] See E. Michael Jones, T he Jewish Revolutionary Spirit and Its Impact on World History (South Bend: Fidelity Press, 2008).

[11] Sarah Elvins and Katherine Parkin, “The Business of Abortion: Referral Services, Cross-Border Consumption, and Canadian Women’s Access to Abortion in New York State, 1970–1972,” Enterprise & Society , Volume 26 , Issue 1 , March 2025 , pp. 197 – 217: Cambridge University Press, January 25, 2024. https://www.cambridge.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Katherine J. Parkin, The Abortion Market: Buying and Selling Access in the Era Before Roe (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2025), kindle edition.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] See John G. West, Stockholm Syndrome Christianity: Why America’s Christian Leaders Are Failing — and What We Can Do About It (Seattle: Discovery Institute, 2025), kindle edition.

[22] “Analysis: Abortion accounts for 22.6% of Planned Parenthood’s clinic revenue,” Liveaction.org, November 19, 2015: https://www.liveaction.

[23] “Record-breaking: Planned Parenthood’s annual abortions reach nearly 400K,” nrlc.org, April 25, 2024: https://nrlc.org/

[24] “Planned Parenthood breaks record: $700M in taxpayer funds and 400k abortions,” Liveaction.org, April 17, 2024: https://www.liveaction.

[25] James Lynch, “Planned Parenthood Facilitated Record Number of Abortions While Receiving Most Taxpayer Funds Ever in 2023-24,” National Review, May 12, 2025.

[26] Two friends of mine recently returned from Korea to the United States and were astonished by the exorbitant medical expenses they incurred for basic prescriptions and routine medical services. One of them was hospitalized for just two days, resulting in a bill exceeding fifteen thousand dollars. The second friend, seeking to document the disparity, even sent me a receipt of his medical charges—totaling two thousand dollars for treatment that would have cost less than two hundred dollars in Korea.

[27] Dana Kennedy, “Planned Parenthood’s stomach-churning emails ‘negotiating’ for fetus donations exposed,” NY Post, November 21, 2024.

[28] For a cultural study on this, see E. Michael Jones, Libido Dominandi: Sexual Liberation and Political Control (South Bend: Fidelity Press, 2022).

[29] J. D. Unwin, Sex and Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1934).

[30] Aldous Huxley, Ends and Means (London: Chatto & Windus, 1946), 311–2.

[31] Richard Dawkins, The Blind Watchmaker (New York: W. W. Norton, 1986), 6.

[32] Sunhye Kim, Na Young, Yurim Lee, “The Role of Reproductive Justice Movements in Challenging South Korea’s Abortion Ban,” Health Hum Rights. 2019 Dec;21(2):97-107. PMID: 31885440; PMCID: PMC6927381: https://pmc.ncbi.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid; my emphasis.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] “Korea’s Unborn Future: Understanding Low-Fertility Treands,” chrome-extension://

[39] Sunhye Kim, Na Young, Yurim Lee, “The Role of Reproductive Justice Movements in Challenging South Korea’s Abortion Ban,” Health Hum Rights. 2019 Dec;21(2):97-107. PMID: 31885440; PMCID: PMC6927381: https://pmc.ncbi.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] “Despite ban removal, women’s access to abortion pills faces legal void in Korea,” Korea JoonAng Daily, October 21, 2015.